GRATIOT COUNTY, Michigan — Dennis Kellogg has farmed for six decades, at times raising dairy cows or hogs and now mostly growing soybeans. A lot has stayed the same in the sixth-generation farmer’s sparsely populated mid-Michigan community, but one thing has changed in a profound way.

Over the last 30 years, the area has increasingly become home to large-scale confined animal feeding operations, commonly called CAFOs, which keep large numbers of animals in tight conditions. The operations typically produce large amounts of waste. Gratiot County, Michigan, where Kellogg farms, now has 24 CAFOs generating a combined total of more than 400 million gallons of manure each year.

“I’m highly concerned about these industrial-sized facilities,” Kellogg said. Living in a region full of CAFOs, he’s seen manure choke local rivers and contaminate land.

As vice president of the Michigan Farmers Union, Kellogg is proudly pro-farm. But he has become a leading voice in trying to stop the latest proposed CAFO buildout.

“I’m not against growth … but concerned about the scale,” he said.

Kellogg is among a group of farmers, citizens and environmentalists seeking to rein in CAFO growth in mid-Michigan. He was one of more than a dozen featured speakers at a public hearing held by Michigan regulators on Feb. 3 over the latest proposed dairy CAFO.

The current source of concern for Kellogg and others in the region is KB Dairy, LLC — a dairy farm now under construction that plans to house up to 3,450 dairy cows, which would generate between 16 million and 34 million liquid gallons of manure annually once operational.

The dairy operators are seeking a National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permit under the federal Clean Water Act as a stand-alone operation. But critics argue the application is an attempt at a legal sleight-of-hand aimed at avoiding stricter regulatory controls.

The address for KB Dairy is the same address as an existing CAFO, De Saegher Dairy, and is owned by the same family. If KB Dairy was considered an expansion of De Saegher Dairy, which already houses 8,000 cows and generates more than 41 million gallons of manure each year, it would create the largest dairy CAFO in the state.

CAFOs in Michigan with over 5,000 animals require a groundwater permit in addition to the surface water permit. Despite being over this total, De Saegher Dairy does not have a groundwater discharge permit but recently applied for one through the state, according to regulators.

Carrie La Seur, an attorney at La Seur Law Firm, said it’s impossible to know what impact De Saegher Dairy may be having on groundwater or how great a risk KB Dairy poses until this permitting is complete.

“There are a lot of hard questions that need to be asked about the impact of the existing CAFO, and of the proposed CAFO and of the new pits that are going to be dug, on public health and on the quality of the drinking water aquifer,” said La Seur, who was previously at Flow Water Advocates, a Michigan nonprofit organization, and led their advocacy against KB Dairy’s permitting.

Concerns about CAFOs and water quality are not limited to Michigan. A report released last week found that industrial animal farming is responsible for about 70% of agriculture’s contributions to nutrient pollution in US waterways — which means it accounts for half of all of the country’s nutrient pollution.

CAFO-heavy states, such as Iowa and North Carolina, have long suffered from water pollution due to large-scale animal farms. In Iowa, for example, industrial animal farms produce more than 100 billion pounds of manure annually. This massive amount of manure represents a 78% increase over the past two decades and is more than 25 times the amount of waste from people in the state annually. And Iowa’s waterways are full of contaminants due to this massive amount of manure, along with its heavy pesticide use, including nitrate levels that frequently exceed health standards.

Meanwhile the Trump administration has loosened regulatory requirements for CAFOs, including winning an appeal last year that maintained exemptions (put in place during the first Trump administration) for CAFOs from reporting releases of air pollutants such as ammonia and hydrogen sulfide.

Local researchers warn the addition of yet another CAFO in Gratiot County will further stress an already manure-saturated region by contaminating already severely impaired rivers and creeks. Studies over the past two decades in local watersheds show the manure contamination is spreading antibiotic-resistant bacteria due to the widespread use of antibiotics on the animals kept in close confinement.

But the owners of KB Dairy say that protecting the environment and waterways is important and that they welcome “oversight and accountability.”

KB Dairy “represents our commitment to build a life in this community,” Kelsey De Saegher, who is a co-owner along with her husband Bram De Saegher of KB Dairy, said in a public hearing on Feb. 3. “We care deeply about the environment and being good neighbors.”

She said “clean water, healthy land and a strong rural community aren’t just an idea to us, [they’re] personal.” Supporters of the dairy said the operation would help boost local jobs while producing healthy, local food.

“The final question that needs to be asked about this facility and so many like it is: how many animals can a watershed support?” La Seur said.

Impaired watershed

Gratiot County allows manure disposal on roughly 55,000 acres — which is the second highest among counties in Michigan. And the two main receiving river systems by KB Dairy — the Pine River and the Maple River — already suffer from excess nutrients, harmful bacteria and other contaminants.

De Saegher Dairy has a history of water quality violations documented by the state, including that it put CAFO waste directly into streams in 2020, and a 2023 notice that alleged the farm failed to update its nutrient management plan, which is supposed to include up-to-date herd numbers, waste storage status and mapping water flow on the farm.

Murray Borrello, a researcher and instructor of geology and environmental studies at nearby Alma College, has studied the watersheds around KB Dairy for decades, and said “there is no site we can find that is not heavily impacted with nutrients and E. coli.” Nutrients, such as nitrogen and phosphorus, are linked to illness, liver and kidney problems and some cancers, while E. coli can cause illness and infections when ingested.

In his most recent study, Borrello and colleagues found that the average phosphorus levels in a creek that winds near several CAFOs (and fields that apply De Saegher Dairy manure) before converging with Pine River were 15 times higher than the maximum concentration for a healthy stream.

E. coli concentrations were nine times higher than Michigan’s health standard for human contact. “These results indicate that nutrients are coming from animal waste and not chemical fertilizers,” the study states. The Pine River watershed is also home to an ongoing massive federal cleanup from a chemical company that dumped toxics in the river for decades.

Borrello said the findings are similar in the Maple River watershed.

“It is clear that the CAFOs that operate or spread manure within the Maple River watershed are contributing antibiotic resistance in the E. coli that we find in these tributaries and in the Maple River itself,” he said. Since 2007, only three out of the more than 30 sites that Borrello and colleagues regularly sampled had an average E. coli level that rendered the water safe to swim in.

E. coli is “pouring into the Pine and Maple (rivers) in damaging quantities” La Seur said, adding that EGLE should require KB Dairy to show that its activities are not going to contribute to the further degradation of those streams. “I haven’t seen that and it is highly unlikely that they can.”

Borrello said samples that he and colleagues have taken from the Pine River and Maple River watersheds, including downstream of De Saegher Dairy, have widespread antibiotic-resistant bacteria, which suggests that concentrated livestock are being given antibiotics and passing it in manure.

“There is no site we can find that is not heavily impacted with nutrients and E. coli.” – Murray Borrello, Alma College

For two common antibiotics used for humans — tetracycline and erythromycin — “all samples we’ve taken at any time over a period of 10 years have been 100% resistant to these antibiotics” in the upper watersheds of the Pine and Maple rivers, Borrello said. The antibiotic-resistant genes are so prevalent in the rivers that “merely fishing in the Pine River results in the transfer of this [antibiotic-resistant E. coli] from fish mucus to human hands,” Borrello and colleagues wrote.

Michigan and Gratiot County are not alone: US communities with CAFO clusters consistently have higher levels of nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus, and antibiotic-resistant bacteria. In Iowa, which has the highest number of CAFOs in the nation, researchers found antibiotic-resistance bacteria in nearly every sample they took from 34 streams.

“CAFOs are the primary source of environmental antibiotic-resistant bacterial pollution,” said Andrew deCoriolis, executive director of Farm Forward. “These farms are causing environmental and human harm and they don’t pay for it.”

Last month the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) data showed sales of medically important antibiotics sold for farm animals increased 16% from 2023 to 2024. Such sales had previously increased 10% between 2017 and 2023.

Bram De Saegher, listed as the main contact for KB Dairy, and Bart De Saegher, Bram’s father and owner of De Saegher Dairy, did not return requests for a comment.

In the application to the state of Michigan, KB Dairy says its discharges will increase the loading of pollutants to the surface waters, and has applied for an exemption for excessive pollution during wet weather. The application lays out a weekly plan to inspect manure storage pits and tanks for leaks and other problems.

Dale George, director of communications with Michigan’s Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy (EGLE), which issues permits for CAFOs, said the agency will consider the existing water quality problems in the river as well as KB Dairy’s manure management plan in finalizing the NPDES permit, which has “dozens of requirements to protect water quality,” he said.

He added that KB Dairy will be required to monitor the volume of CAFO waste discharged and have the waste analyzed for E. coli, phosphorus, ammonia, nitrogen and total suspended solids. Many CAFOs adopt buffer zones, additional testing, and other conservation measures beyond state standards. The KB Dairy application says “there are no formal conservation practices on the farm.”

When asked about KB Dairy being an expansion of De Saegher Dairy since they share an address, George said “the same address does not constitute same ownership.”

When pressed at the Feb. 3 hearing about how the state would ensure they are not acting as one farm moving forward, Samantha Chadwick, an environmental quality analyst with EGLE, said the agency would conduct “regular inspections of the permitted facility once in a five-year period … then evaluate if they’re operating two separate entities.”

At a watch event for the hearing at nearby Alma College, residents groaned and whispered after Chadwick’s statement. “People are starting to realize that their cherished way of life is at risk due to these operations,” La Seur said.

Manure digester economics

Part of the plan for KB Dairy involves the use of anaerobic digesters operating at De Saegher Dairy that will treat the animal waste while also creating biogas, a mix of mostly methane and carbon dioxide that can be sold for use as a natural gas substitute.

Advocates of biogas and farm digesters say the technology mitigates agricultural pollution while also creating a usable source of energy. But critics say the use of farm digesters incentivizes the addition of animals to already large farms without actually providing significant environmental benefits.

The Michigan fight comes as manure-to-gas digesters are on the rise throughout the US and the Trump administration has given mixed signals on whether it wants to support the still-nascent industry.

Some of KB Dairy’s waste will be sent to the anaerobic digesters at De Saegher Dairy, according to KB Dairy’s application to the state. Such digesters are becoming increasingly common in the US at large-scale livestock farms that use bacteria to break down large amounts of animal manure and turn it into “biogas”, which is a mix of mostly methane and carbon dioxide and used in some vehicles and as a natural gas substitute.

Cheryl Ruble, who is on the committee of Michiganders for a Just Farming System, alleged that KB Dairy is an effort to feed the De Saegher Dairy manure digesters. “You’ve heard the expression putting the cart before the horse? I call this putting the digester before the cow,” she said.

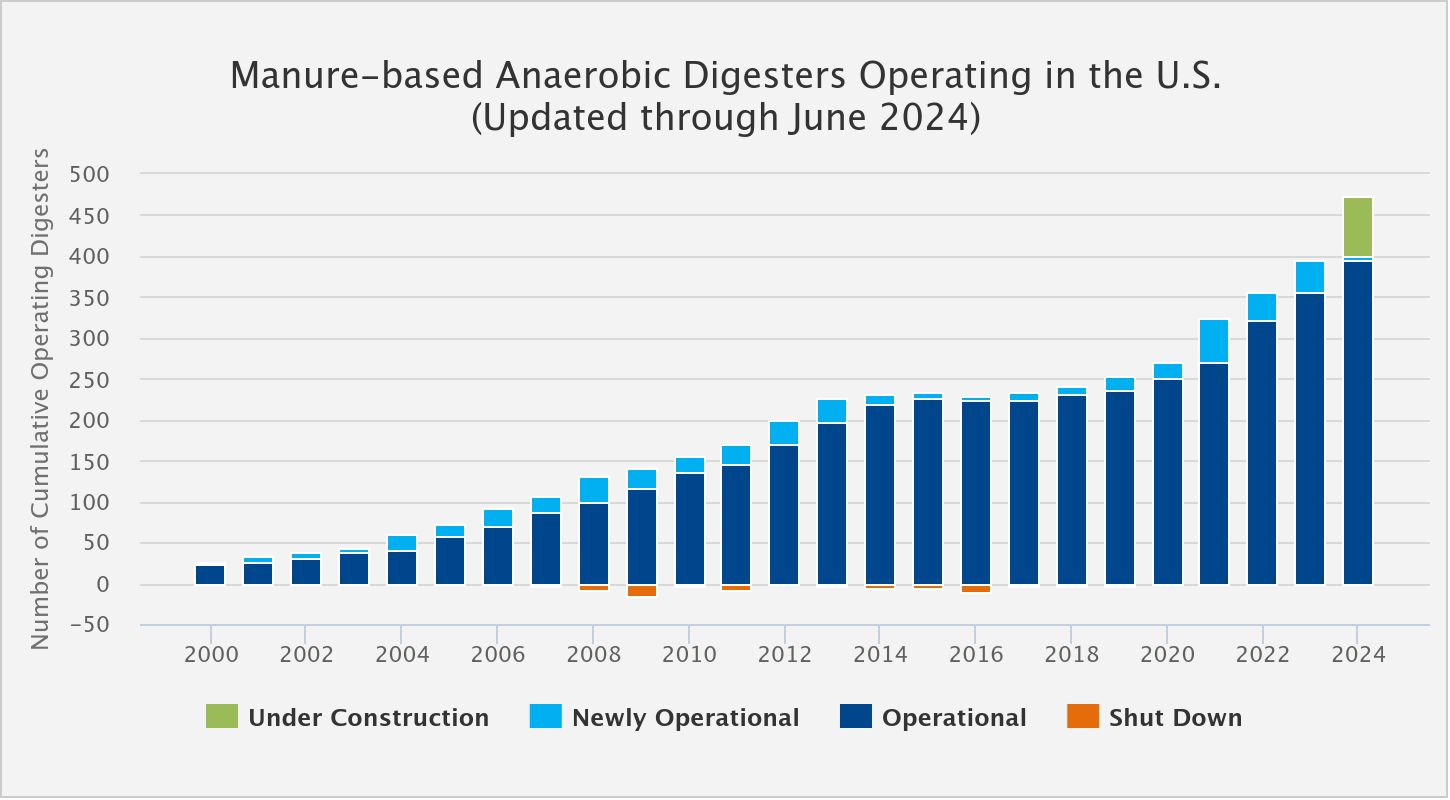

There has been a flood of new US manure digesters. There are an estimated 400 manure-based digesters operating in the US (85% are dairy farms), with more than 70 under construction, representing a 55% increase over the past decade, according to the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The agency estimates manure digester systems would be feasible at more than 8,000 dairy and hog farms.

Aaron Smith, a researcher and professor of agricultural and resource economics at the University of California, Berkeley, said manure digesters are creating incentives for CAFOs to expand or concentrate but it’s unclear if those incentives alone are enough to spur expansions.

“People in industry will tell you that no farmer is going to start up a dairy farm just for the purpose of farming manure. But would they expand herd size on the margin? That seems plausible,” he said.

Jonah Greene, a research scientist at Colorado State University, said he and colleagues found that dairy farms start to see the financial benefits of adding a manure digester once they get in the 2,000 to 3,500 range of cows.

“That’s when a system starts making money or that’s when the cost of the gas that you’re producing starts to become competitive with other options on the market,” he said, adding that the viability of systems is also heavily influenced by incentives like renewable energy credits. KB Dairy’s application said it will house between 2,000 and 3,450 cows.

In sending its waste to De Saegher Dairy’s digesters, KB Dairy “will receive the same amount of waste back and will transfer that waste to other parties for the purpose of land application,” George said. De Saegher Dairy failed to submit air quality reports for its digesters in 2023, and had monitoring failures in 2024, according to state documents.

The Michigan Farm Bureau, which did not respond to requests to comment on the KB Dairy CAFO, has supported the expansion of manure digesters in Michigan, saying they will be “a vital part of Michigan reaching its climate and sustainability goals, empowering communities to create green energy while reducing carbon footprints,” in a white paper last year.

“People in industry will tell you that no farmer is going to start up a dairy farm just for the purpose of farming manure. But would they expand herd size on the margin? That seems plausible.” – Aaron Smith, University of California, Berkeley

The future of manure digestion in the US remains unclear as the Trump administration has sent mixed signals on biogas — extending tax credits that benefit manure-to-gas digesters in the “One, Big Beautiful Bill,” but also removing the eligibility of biogas-generated electricity’s eligibility for the federal biofuels program. And just last month the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) paused a loan program aimed at promoting anaerobic digesters — many of which are issued for large-scale farms that turn animal waste into gas — citing “underperformance, loan delinquency and operational failure.”

A lot of the digester incentives are from public dollars. Smith said the “only thing that makes digesters economically viable is government support. It costs nine to ten times as much to produce gas from a digester as it does to pull it out of the ground.”

Emissions reductions and leftover nutrients

Patrick Serfass, executive director of the American Biogas Council, said farmers expand due to economics — not the benefits from manure digesters, which he said are a way to reduce contamination and give farms useable nutrients. “If you can make sure the manure is fully digested in the controlled environment, then the material, the solids and liquids that you end up with, are not going to produce more gases or they’ll produce significantly less gases than they would have otherwise,” he said. “And that material has now been converted into nutrient-rich soil amendments that you can do lots of different things with.”

“What we’re doing with these biogas systems is actually one of the oldest processes in the universe,” he added.

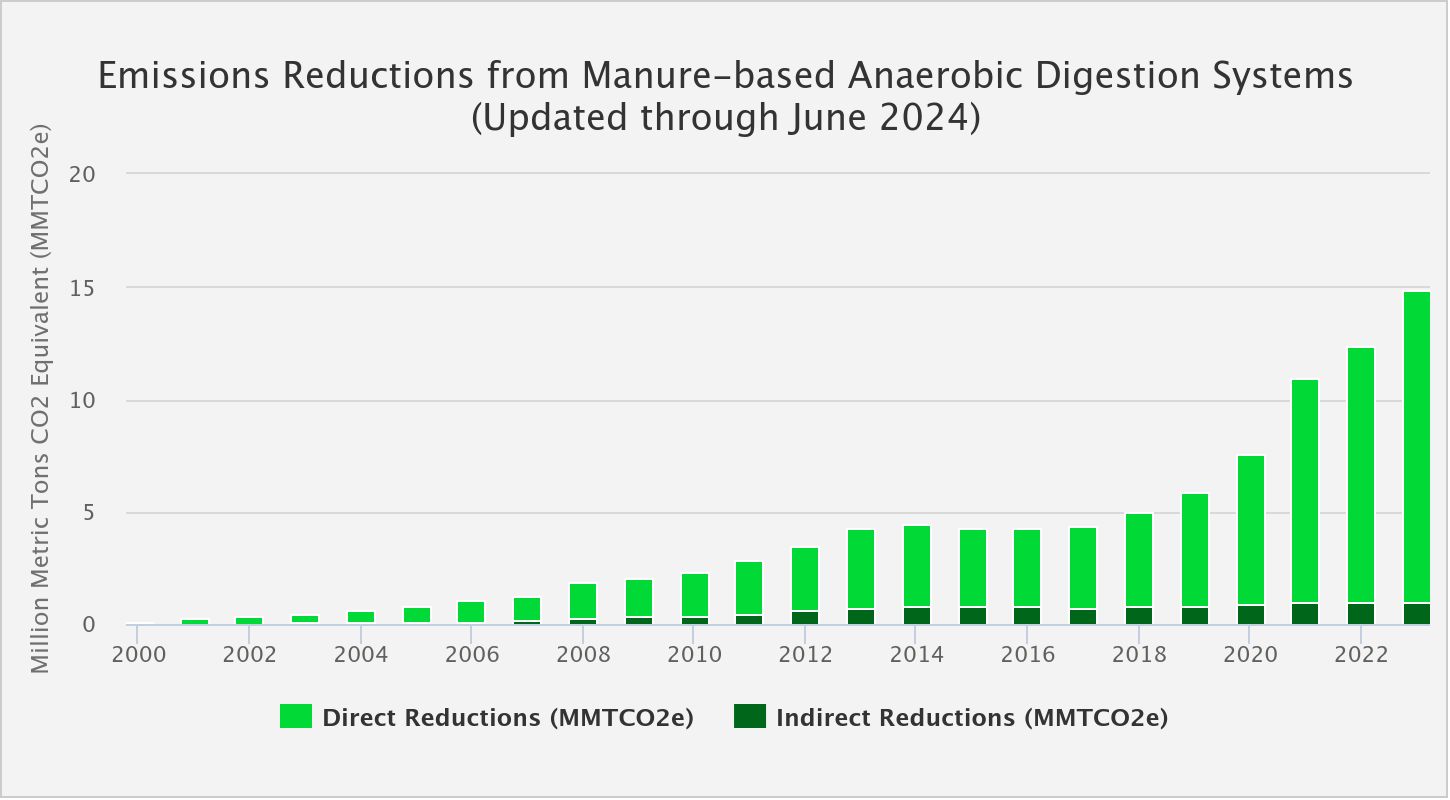

Manure digesters reduced greenhouse gases by more than 13 million metric tons in 2023, according to the most recent data available from the EPA. And the stuff left over after the digester does its work — called “digestate” — can augment farm soils. A 2025 study on an Iowa farm that used digesters and spread digestate found that soil organic carbon and soil fertility both benefited more from digestate than just spreading raw manure.

“Integrating anaerobic digestion on farms can help reverse soil degradation and enhance agricultural sustainability,” the authors wrote.

But critics warn that manure digesters can also worsen pollution. Last year Johns Hopkins researchers reviewed the literature on manure digesters and found that, when spread on fields, digestate can contaminate local waterways with phosphorus, nitrogen and pathogens.

“Digestate may pose a higher risk for soil and water quality because the elements in it are more soluble compared to undigested manure,” the authors wrote, also noting that the digesters do reduce greenhouse gas emissions but, due to leaks the reductions are modest.

Permitting decision

George said a final permit decision will not occur until EGLE considers all public comments, which the agency is accepting until Feb. 13. However, the state seems intent on issuing the permit. KB Dairy’s application “meets all regulatory requirements, and we’re required to issue permits if they meet those requirements,” Rebecca Maurer, who issues permits through EGLE’s water resources division, said at the Feb. 3 hearing.

After hearing several concerns from neighbors throughout the hearing, Kelsey De Saegher reiterated their commitment to farming in a sustainable way. “We live here, raise our children here and we drink the same water as everybody else in this community.”

Kellogg said Michigan’s Farmers Union remains committed to the rights of farmers, but is an advocate for “the family farm unit.”

“We define that as what a family can operate themselves. We’re seeing that highly concentrated units are displacing our family farms.”

Featured photo: KB Dairy is constructing buildings on land bordering De Saegher Dairy while it awaits its permitting. (Credit: Jeff Brooks-Gillies/The New Lede)