In Iowa, many rivers and lakes improve briefly, then fall back into impairment

When Kim Hagemann moved to Iowa in the late 1980s, the state’s lakes and parks were among the first places she explored.

She had come from Wisconsin to attend graduate school at Iowa State University, newly married and short on money. For recreation, Hagemann and her husband drove to public lakes and parks across the state, places that, on paper, defined Iowa’s natural landscape.

But the outings quickly became discouraging. “After you’ve gone to your third park and it’s smelly and there’s nobody on the beaches, you start to get discouraged,” she recalled.

Nearly four decades later, Hagemann, now retired and living in rural Polk County, said her view of Iowa’s water has not improved. “Here we are in 2025, and the water is actually worse,” she said during an interview last month.

Hagemann’s experience mirrors what state data shows.

An analysis by Investigate Midwest, based on the Iowa Department of Natural Resources’ biennial impaired and delisted waters lists, shows that progress in removing river segments from the impaired waters list has been limited over the past eight years.

While 2018 marked a high point, when 12% of impaired river segments were delisted, subsequent cycles saw far smaller shares, with about 2% delisted in 2020 and roughly 7% in 2022.

Lake segments showed a different pattern. Beginning in 2020, a higher proportion of impaired lake segments were reported as partially or fully recovered, with 32% delisted in 2020 and 35% in 2022.

However, being removed from the impaired waters list does not necessarily mean a river or lake has fully recovered.

Of the 17 rivers and lakes removed from the 2016 impaired water report, seven showed only partial improvement, continuing to struggle with certain uses or pollutants even as conditions improved elsewhere. A similar pattern emerged in 2022. Of the 54 river and lake segments removed after meeting water-quality standards, 22 had not fully recovered.

In those cases, impairments persisted across multiple designated uses, within a single use affected by more than one pollutant, or across multiple uses affected by multiple pollutants.

The analysis excluded fish kill events, which are considered isolated incidents rather than indicators of long-term water-quality conditions.

Michael Schmidt, general counsel at the Iowa Environmental Council (IEC), said the pattern reflects how water pollution is — and is not — regulated.

Under the federal Clean Water Act, most farm field runoff is treated as nonpoint-source pollution and is generally exempt from the permit requirements that govern industrial and municipal “point source” discharges. As a result, Schmidt said, improvements tied to regulated point sources tend to persist, while pollution from agriculture can fluctuate with weather and farming practices.

Polluted runoff occurs when rain or melting snow flows across the land instead of soaking into the soil, carrying fertilizers, manure and other contaminants along the way. Those pollutants are eventually washed into rivers, lakes, wetlands and other waterways, and in some cases into underground sources of drinking water. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, runoff from agricultural land is the leading cause of impairments in rivers and lakes.

“You might have water that is cleaner in dry years, so it gets delisted, and then is more polluted in wet years and gets relisted,” Schmidt said.

One lake, Schmidt said, illustrates how those wins can crumble.

At Lake Darling in southeast Iowa, the state undertook a major restoration project funded by federal, state and local sources, investing about $13 million, including almost $7.3 million for watershed and in-lake improvements.

A 2024 study by Drake University, commissioned by the Iowa Department of Natural Resources, found that conditions within the lake, including low oxygen levels and elevated phosphorus near the bottom during summer months, may be contributing to recurring algal blooms.

“The growth of cyanobacteria in the lake and E. coli in beach sands is likely being driven by nutrient loading from the watershed,” the report said, adding that the implementation of best management practices would help ensure long-term water-quality improvements.

The problem, Schmidt said, was not the work done within the lake itself, but what remained upstream.

“We just addressed what was in the lake,” he said, but “we didn’t clean up the pollution sources upstream.”

Last year, Investigative Midwest reported that nearly eight out of 10 river segments in Iowa have remained continuously impaired for at least a decade, according to an analysis of state reports. During the same period, 43% of lake segments experienced similar long-term impairment.

In fact, 65 river segments (15%) and six lake segments (11%) have fallen short of a key water quality standard for a specific use and impairment for at least 20 years.

Taken together, the data suggest that while some Iowa waters show signs of improvement, lasting recovery remains elusive, and that for many rivers and lakes, coming off the impaired list is not the end of the story.

State monitoring captures only part of what is happening in Iowa’s waterways.

The Iowa DNR assesses slightly more than half of the state’s designated water bodies. In 2024, 27% of these segments were classified as healthy waters, while just over half were categorized as impaired. Meanwhile, slightly more than one-fifth require further investigation, as they are identified as “potentially impaired.”

Heather Wilson, the Midwest Save Our Streams coordinator at the Izaak Walton League of America, a nonprofit focused on the conservation and sustainable use of natural resources, said Iowa’s water pollution crisis is not new, but that last year feels different.

She said the issue has drawn an unusual level of public engagement.

“More than any year [2025], citizens and people who are part of these grassroots organizations should feel more empowered than ever,” Wilson said. “More and more people are becoming engaged.”

Wilson pointed to a surge in public participation following a series of high-profile events, including the lawn-watering ban in central Iowa, the release of the Central Iowa Source Water Research Assessment, and the fish kills in the Nishnabotna River in southwestern Iowa. Through the league’s Nitrate Watch program, she said, the number of volunteers requesting test kits and reporting data has increased significantly.

“What that represents is people who are becoming more informed,” she said. “They’re learning about their local water quality and the impacts that that might have on their health.”

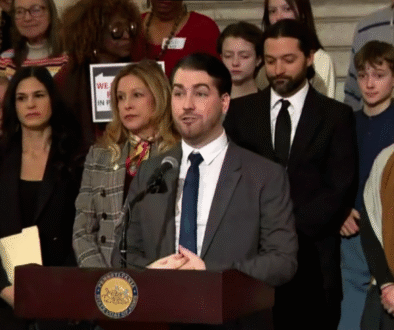

Lawmaker changes strategy in pushing for new regulations to improve Iowa lakes and rivers

Despite years of analysis and repeated findings, Schmidt said, many of the policy debates around water quality have gone unresolved.

“The legislature has not been interested in doing more, at least the legislative leadership, or the majority of the legislature, has not taken action,” Schmidt said.

Schmidt said the state has long known what would reduce nutrient pollution. Iowa’s Nutrient Reduction Strategy, adopted in 2013, outlined a path forward, but progress has been limited and legislative action has not followed.

The strategy aims to cut annual nitrogen and phosphorus losses by 45%. For agriculture, which is considered a nonpoint source of pollution, the strategy relies on the voluntary adoption of conservation practices intended to reduce the amount of nutrients that leave farm fields into nearby waterways. For point sources, including certain municipalities and industrial facilities, the strategy calls for evaluations of existing nutrient controls and, where feasible, upgrades to treatment capacity.

“We identified what we should do to reduce nutrients in 2013,” Schmidt said. “We are not making great progress, so we need to be doing more.”

That lack of movement has been visible in recent legislative sessions. Last February, Sen. Art Staed, a Democrat from Cedar Rapids, again introduced the Clean Water for Iowa Act, a bill he had previously proposed that would require large animal feeding operations to obtain water pollution permits and conduct effluent monitoring. As in prior years, the proposals did not advance.

“More than any year [2025], citizens and people who are part of these grassroots organizations should feel more empowered than ever. More and more people are becoming engaged.” – Heather Wilson, Izaak Walton League of America

For 2026, Staed said he is trying a different strategy after repeated legislative setbacks. Instead of reintroducing a single water-quality bill, he said he is breaking the proposal into at least a dozen narrower measures, focused on better monitoring of the water-quality system, stricter enforcement, giving the Department of Natural Resources more authority and improved field practices, including buffers between row-crop farmland and waterways.

Staed said the bills are still being drafted and that the volume of legislation this year has slowed the process, but expects most to be ready to file next week. The goal, he said, is to move individual provisions that could attract bipartisan support, as broader reforms have continued to stall.

“It is my fundamental belief that all Iowans deserve access to clean water. If there’s one bit of silver lining to come from our state’s current predicament, it’s that water quality is now front of mind for far more Iowans than in recent memory,” he said.

“The question now to lawmakers in 2026 is whether or not we can meet the moment.”

Concerns about water quality have increasingly intersected with broader public-health anxieties in Iowa. The state has the second-highest age-adjusted rate of new cancers diagnosed and is one of only two states with a rising age-adjusted rate of new cancers. While advances in treatment have increased the number of cancer survivors, researchers and physicians have warned that the trend also brings rising costs and renewed urgency to better understand potential environmental risk factors.

Those concerns gained momentum in 2025 among community groups, researchers, advocates and lawmakers, as questions mounted about how pollution could affect long-term health outcomes. This month, at the opening meeting of the Iowa Senate Natural Resources and Environment Committee, water quality dominated lawmakers’ remarks.

Staed, a member of the committee, said the heightened attention reflects growing political awareness but no meaningful change. “They’ve done a lot,” he said, referring to state leaders’ water-quality initiatives. “But it’s not enough to change the trajectory of nitrates in the water, the quality of water, and of course, rare cancer rates, and so on, that might be part of it.”

Looking ahead to the 2026 legislative session, which began Jan. 12, advocacy groups including the IEC have outlined a short list of priorities they say could shape the debate over water-quality policy.

At the top of the list is restoring funding for Iowa’s water monitoring network, the Iowa Water Quality Information System. The network, led by the University of Iowa with support from federal agencies, uses real-time sensors to track nitrates, phosphorus and other pollutants at about 60 sites statewide.

State funding for the system ended in 2023, forcing the network to rely on temporary private and local support. Sensor coverage has since declined, and university officials have warned the system could be shut down by mid-2026 without new funding.

The council is urging lawmakers to restore funding for the Iowa water monitoring network. About $600,000 a year is needed to support the system. The original appropriation was $500,000, which would not be sufficient to fully reinstate the network’s previous capacity of 70 sensors; the IEC cited inflation as the reason the higher annual amount is now required.

Kerri Johannsen, senior director of policy and programs at the IEC, said restoring funding for water monitoring network is the group’s top priority this year.

“It’s common sense,” Johannsen said. “[It’s] essential to even have a benchmark … know where we’re going and if what we’re doing is working.”

Johannsen said the council is also pushing for expanded monitoring tied to pollution sources, including closer oversight of large animal feeding operations to detect whether waste is leaking into groundwater. Without consistent monitoring, she said, it is difficult to identify problems early or stop pollution where it is occurring.

Another priority is protecting Iowa’s waterways from coal-plant pollution, including proposals to restrict or prohibit coal-ash discharges into state waters.

Staed said public pressure on water quality issues is unlikely to fade.

“This issue isn’t going away,” he said. “Our farmers want to be good stewards of the land, and their voluntary efforts have helped, but the state needs to do more. More and more Iowans are speaking up on this issue and I’m hopeful that their voices can finally lead to a shift at the Capitol; that we can finally begin to address the problem and bring clean water to Iowans in every corner of the state.”

This article first appeared on Investigate Midwest and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Featured photo: An outcropping is seen along an ADA fishing trail at Lake Darling State Park in Brighton, Iowa, on Wednesday, Sept. 17, 2014. photo by Jim Slosiarek, The Gazette.