RFK’s new dietary guidelines — “dream come true” or “a real mixed bag”?

By Shannon Kelleher and Carey Gillam

New US dietary guidelines released by the federal government this week received mixed reactions from the health community, with many praising the move to explicitly advise against consuming highly processed foods in favor of whole foods but others concerned about a recommendation to consume red meat, which is linked to heart disease, as well as full-fat dairy, a source of saturated fat.

The updated Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA), published Jan. 7 by the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the US Department of Agriculture (USDA), advise consumers to avoid foods with added sugars and highly processed foods, such as hot dogs and frozen meals that contain chemical preservatives, emulsifiers and sweeteners and other additives, aligning with a key priority of the Make America Healthy Again movement (MAHA).

The guidelines, which are updated every five years, also encourage eating “real foods,” including “high-quality, nutrient-dense protein from both animal and plant sources,” dairy, vegetables and fruits, healthy fats and whole grains.

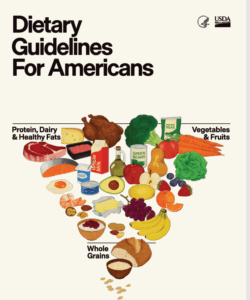

The rollout includes a new food pyramid – an inverted triangle that features mostly “protein, dairy & healthy fats” and “vegetables & fruits,” with “whole grains” occupying a smaller portion.

“It’s a dream come true that the government has finally told people to eat more real food,” said Vani Hari, an author and food activist known as the ‘Food Babe’ who is active in the MAHA movement. “This is something I’ve been working on for the last decade. It’s so good for America.”

The DGA report calls the guidelines “the most significant reset of federal nutrition policy in our nation’s history.”

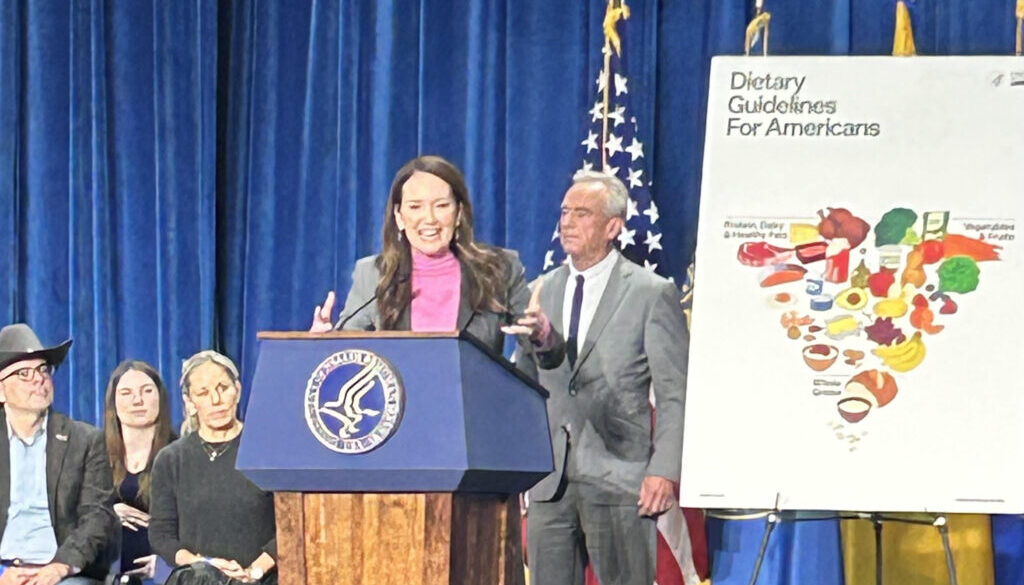

At an event in Washington, DC on Thursday, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the US Secretary of HHS, said the guidelines would “revolutionize” the nation’s food culture.

“Our government has been lying to us to protect corporate profit-taking, telling us that these food-like substances were beneficial to our health,” said Kennedy. “Federal policy promoted and subsidized highly processed food and refined carbohydrates and turned a blind eye, with cataclysmic consequences. The new guidelines recognize that whole, nutrient-dense food is the most effective path to better health and to lowering healthcare costs.”

The prior guidelines issued in 2020 also called for Americans to build their diets around nutrient-dense foods and beverages with “core” elements including vegetables, fruits, lean meats, poultry, eggs, beans, peas and lentils.

But the new guidelines differ sharply by recommending red meat (the previous guidelines suggested lowering consumption of red and processed meats), suggesting full-fat dairy products instead of fat-free or low-fat versions and recommending 1.2 to 1.6 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight per day, an increase from the Recommended Dietary Allowance of 0.8 grams per kilogram of body weight.

Another distinction: The new guidelines explicitly advise consumers to avoid highly processed foods, while the previous guidelines called for lower consumption of sugar-sweetened foods and beverages and refined grains.

The American Medical Association said in a statement that it applauds the guidelines for “spotlighting the highly processed foods, sugar-sweetened beverages, and excess sodium that fuel heart disease, diabetes, obesity, and other chronic illnesses,” adding that they offer “clear direction patients and physicians can use to improve health.”

The guidelines were also praised by the Food Industry Association (FMI), a national trade group, which said in a statement that the guidelines offer a chance “to meet consumers where they are and lean into the expertise and guidance of registered dietitians across the industry.”

However, critics questioned the scientific rigor of the new guidelines and move to recommend red meat, which has been linked to heart disease, bowel cancer and other ailments, as well as other animal products tied to health concerns.

“While the meat and dairy industries may be excited about the new food pyramid, the American public should not be,” the Center for Public Interest (CSPI) said in a statement, calling its guidance on protein and fats “at best, confusing, and, at worst, harmful.”

“It’s one thing to advise against consuming unhealthy, highly processed foods but another to imply that any food that isn’t highly processed must be healthy,” said Eva Greenthal, a senior policy CSPI scientist. “Unfortunately, the new DGA does both and misrepresents foods like red meat, full-fat dairy, butter, and beef tallow as healthy despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary.”

While the American Heart Association (AHA) said in a statement that it approves of many points included in the guidelines, including eating more vegetables, fruits and whole grains and avoiding highly processed foods, the organization fears the guidelines may nudge consumers to eat more than the recommended daily limits for sodium and saturated fats, which drive heart disease. The AHA added that it encourages eating low-fat and fat-free dairy products rather than full-fat versions.

Two Harvard researchers who served on a DGA advisory committee said in a press conference Thursday that the new guidelines have multiple flaws that could lead consumers to make dietary choices that lack adequate balance and optimum nutritional diversity.

One concern is a lack of limits or detailed food choice guidance within protein recommendations, said Deirdre Tobias, an obesity and nutritional epidemiologist, is an assistant professor in the Department of Nutrition at Harvard Chan School and an assistant professor of medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School.

One of the biggest deviations from the prior DGA and from the advisory committee report is a lack of limits on specific types of protein, she said. There are no limits within protein for red meat, for example.

“Variety is essential” when it comes to protein, she said. “Having protein … only come from, you know, beef every day or chicken or just eggs really runs the risk of creating an overall pattern very low in fiber.”

Under the new guidelines, “one could meet the goals for protein foods entirely from something like red meat or chicken or pork, or sources that would make them sort of essentially lack fiber and these nutrients from the plant-based sources altogether,” Tobias said.

“If people are to eat more protein from meat sources it puts people at risk of exceeding limits for saturated fat, which is a significant risk for coronary heart disease and cardiovascular disease, she said.

The new guidelines come after the Trump administration scrapped an earlier version finalized in December 2024 under the Biden administration. In a March 2025 statement announcing plans to continue working on the guidelines, Kennedy said the USDA and HHS would “make sure the dietary guidelines will reflect the public interest and serve public health, rather than special interests.”

But several of the researchers that helped develop the new guidelines have been linked to the beef and dairy industries.

On Wednesday, CSPI and the Center for Biological Diversity released “uncompromised” dietary guidelines that “demonstrate what the federal government’s overarching Guidelines for healthy dietary patterns could have looked like if the Trump administration had not strayed from its mandate … to publish Guidelines based on the preponderance of the evidence,” the groups write.

The groups’ version of the dietary guidelines calls for most people to increase consumption of plant-based proteins, including beans, lentils, nuts and seeds, while decreasing their red and processed meat intake. The report notes that while these guidelines do not directly recommend reducing ultra-processed food consumption “due to inconsistent definitions and study methods,” they suggest eating whole, minimally processed foods.

Featured Image: USDA Secretary Rollins and HHS Secretary Kennedy present the new dietary guidelines at an event in Washington, DC on Jan.8. (Credit: Shannon Kelleher, The New Lede)