Study maps factory farm hotspots as federal court tosses emissions lawsuit

Listen to the audio version of this article (generated by AI).

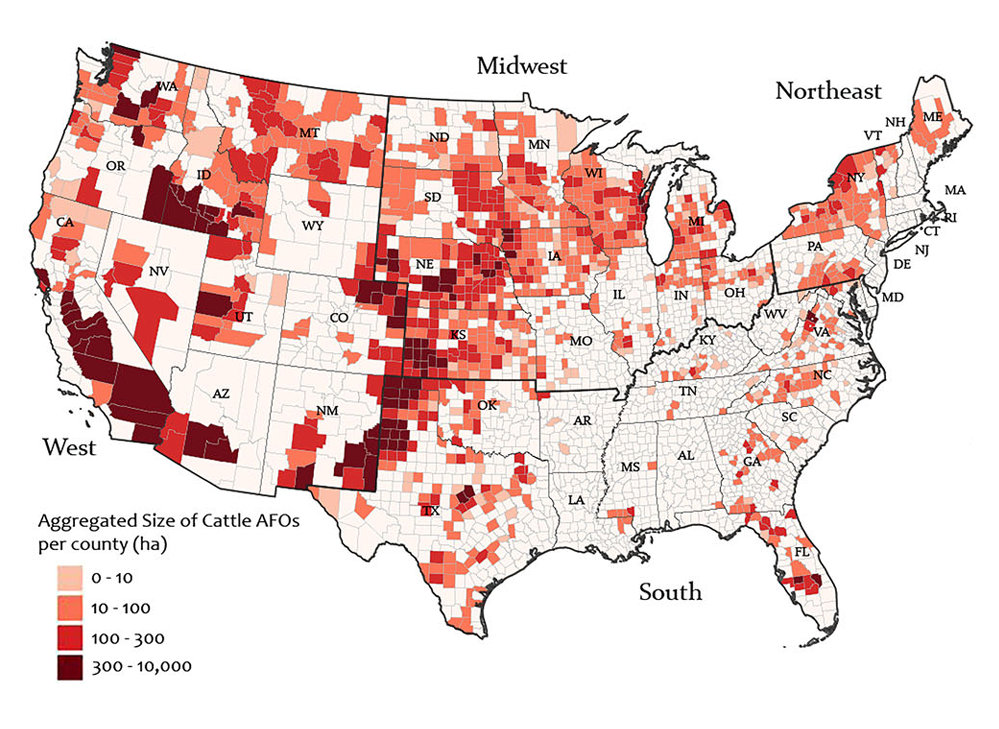

Roughly a quarter of the nation’s large cattle, dairy and hog farms are located in just 30 US counties, a new satellite-mapping study has found. The research also links large farms — whether in these dense hotspots or scattered elsewhere — to elevated air pollution.

The study supports concerns about the environmental impacts of factory livestock farms, which drive up air pollution levels by kicking up dust and ammonia in the massive amounts of manure onsite. It also comes on the heels of a federal ruling last week that supported exemptions for animal feeding operations from letting state and local officials know about “dangerous” pollutants, including air emissions.

The ruling sided with the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and industry farm groups in continuing an exemption under the Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act, and tossed a lawsuit filed by environmental groups.

The environmental groups alleged that the EPA “acted arbitrarily and capriciously by failing to consider the public’s right to access information” when the agency determined animal waste air emissions no longer needed to be reported.

The new study, published in the peer-reviewed journal Communications Earth & Environment, is the first to nationally map out the size and location of these farms — called animal feeding operations or AFOs (defined as a livestock operation where animals are kept and fed for more than 45 days in a year) — and estimate their contribution to nearby PM2.5 emissions.

PM2.5 are tiny particulate air pollutants 30 times smaller than the width of a human hair and inhalation of them has been linked to asthma, heart and lung problems and preterm births.

“The meat you eat comes from somewhere. It takes up a lot of space and produces a lot of pollution,” Benjamin Goldstein, an assistant professor at the University of Michigan School for Environment and Sustainability and senior author of the new study, said in a statement. “And somebody else … has to bear that pollution.”

While experts say the new study is underestimating total AFOs, it adds to evidence that these large livestock operations — which, when large enough, are called concentrated animal feeding operations or CAFOs — are densely clustered in communities and fouling the air around them.

This study highlights “the inadequacy of existing pollution regulations … [and] demonstrates the urgent need for policy that limits the extreme concentration of concentrated animal feeding operations in rural communities,” Chris Hunt, deputy director of the Socially Responsible Agriculture Project (SRAP), said.

Clustered in certain states, counties

The researchers used existing federal and community data of AFOs and went through satellite data of every US county in the lower 48 states to locate the operations. Their totals are lower than federal estimates.

“We’re not claiming this includes every AFO in the US, but it’s a large enough sample to draw conclusions with confidence,” Dimitris Gounaridis, an assistant research scientist at the University of Michigan School for Environment and Sustainability and co-author of the new study, said in a statement.

Most of the cattle AFOs were in the Midwest and West, which together account for eight of the top 10 cattle AFO states. The top five states were California, Wisconsin, Nebraska, Idaho and Iowa.

This “demonstrates the urgent need for policy that limits the extreme concentration of concentrated animal feeding operations in rural communities.” – Chris Hunt, SRAP

Overall, just 21 counties have 26% of the total cattle AFO operations, and many counties are packed with these industrial farms.

“Five of the top ten counties (Tulare, Stanislaus, Merced, Kings in California, and Weld in Colorado) have more area dedicated to cattle AFOs than some of the top states,” the authors wrote.

A majority of hog AFOs were in the Midwest and South. The top five states were Iowa, North Carolina, Minnesota, Oklahoma and Missouri.

Just 28 US counties have 41% of the hog AFOs, and the top ten states account for 86% of the total operations in the US.

Dr. James A. Merchant, a professor emeritus at the University of Iowa departments of Occupational and Environmental Health and Internal Medicine, said the study is a useful sample of AFOs but “it is not clear if it is representative,” adding that the paper also doesn’t include large poultry farms, which are a potent source of ammonia and drive PM2.5 in AFO-dense areas.

But he said that “focusing on PM2.5 is the right environmental exposure.” The researchers found PM2.5 levels were roughly 28% higher near cattle feeding operations and 11% higher near hog operations compared to similar counties without AFOs. Large livestock farms drive up PM2.5 levels through ammonia in the massive amounts of manure and dust.

“It lingers in the air and can get really deep into your lungs and create scar tissue. It’s nasty stuff. There are really no safe levels of it,” Goldstein said.

In addition, an estimated 1.3 million people who do not have health insurance live within 10 miles of these cattle and hog AFOs.

“Industrial livestock operations have long been known to pose a serious threat to public health and the environment, causing pervasive — yet often overlooked — environmental injustice,” Hunt said.

Challenge to industrial farm air pollution shot down

Environmental groups have for years pushed for more air pollution regulation at AFOs — and last week that effort suffered a major blow. A federal judge shot down a lawsuit brought by Rural Empowerment Association for Community Help and nine other organizations, which were pushing for the EPA to mandate air emissions reporting from animal feeding operations. “Emissions generated from animal waste at CAFOs are highly toxic and are sickening communities across the country,” the original lawsuit stated.

“It lingers in the air and can get really deep into your lungs and create scar tissue. It’s nasty stuff. There are really no safe levels of it.” – Benjamin Goldstein, University of Michigan

US District Judge Timothy Kelly last week, however, wrote that Congress exempted air pollution from animal waste from needing an EPA notification under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA).

“Congress’s CERCLA exemption for air emissions from animal waste at farms meant such releases were also exempted from [the Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act] … EPA had no leeway to consider the public’s right to access information,” Judge Kelly wrote.

The study authors point out that the livestock industry has “stymied attempts” to include AFOs in air pollution regulations, arguing that links between these facilities and air pollution are inconclusive.

“Our study clearly demonstrates the existence of this link. Residents, NGOs, and local governments should advocate for national regulations on PM2.5 emissions from AFOs based on our findings,” they wrote.

Featured image: An Oregon Department of Agriculture employee inspects a concentrated animal feeding operation. (Credit:Oregon Department of Agriculture)