Industry braces for change as feds target synthetic food dyes

Would you eat a beet-flavored gummy? How about a hint of carrot in your soda?

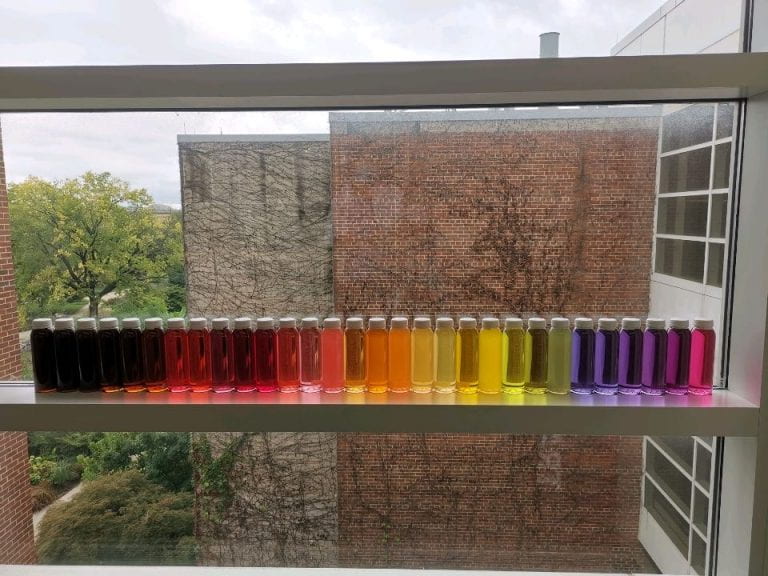

Food manufacturers believe the answer to both questions is ‘no.’ As synthetic food dyes increasingly come under public and federal scrutiny over health concerns — in part bolstered by the Make America Healthy Again, or MAHA, movement — slightly altered flavors in some of Americans’ favorite snacks are just one of the concerns and challenges with switching to dyes made from radishes, cabbages, beets, carrots, butterfly pea flower extract, turmeric, paprika, hibiscus and other natural foods.

“One of the hurdles is simply: do consumers accept these?” said Michelle Frame, president and founder of Victus Ars, Inc., a food development and production lab focused on sweets and making supplements and pills more palatable.

Officials from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) announced last month that they would work with food manufacturers to phase out synthetic food dyes made from petroleum. The federal effort comes as several states have already moved to ban or limit synthetic dyes in foods, particularly foods served in schools.

While the changes should make foods healthier, it remains unclear how the switch will happen and what impacts it could have on the food industry and consumers. Dyes play a large role in the creation of candy, sodas, cereals, sports drinks and other processed foods, and switching to the natural dyes presents a number of challenges.

Experts say companies face several hurdles if there is a broad switch to natural dyes, including availability, stability and taste issues. And the likely disruptions to supply chains, recipes and manufacturing processes will almost certainly bring cost increases to food makers — and consumers, they warn.

While FDA Commissioner Marty Makary said at the April 22 press conference that this would not increase food prices, Frame estimated prices could climb between 5-20%.

“Prices will go up,” she said.

“Years and a lot of money”

It’s unclear what percentage of dye-containing foods are currently made with natural dyes, said Kantha Shelke, a food researcher, senior lecturer at Johns Hopkins University and founder and principal of Corvus Blue LLC, a food science firm. But even prior to the recent government announcement, there were signs of growing efforts to make the switch from synthetics.

PepsiCo, for example, already counts more than 60% of its US food products as free of artificial colors, and told investors last month that brands like Lays and Tostitos would be made without artificial colors by the end of this year. The company said it expects to offer consumers natural color options in all of its portfolio of products within the next couple of years.

Still, rapid change will be hard to achieve for many companies, experts say.

“The initiative to reformulate without synthetic dyes will take years and a lot of money,” said Shelke. “Currently, the volume of natural alternatives simply cannot meet the demand.”

The push for ingredient changes comes as food and agricultural companies are already signalling reluctance to invest in expanded operations due to Trump administration tariffs, which have triggered predictions of a recession and general economic turmoil.

“Currently, the volume of natural alternatives simply cannot meet the demand.” – Kantha Shelke, Corvus Blue LLC

The federal push to eliminate synthetic dye additives is driven by scientific research linking the dyes to a range of children’s health problems, including increasing risk for behavioral issues such as Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). As part of the planned phase out, the FDA said it is “fast-tracking the review” of several natural alternatives made from plants that companies could use as replacements for synthetic dyes.

The announcement said the agencies would revoke authorization for two food dyes (Citrus Red No. 2 and Orange B), and work with industry to eliminate six other synthetic dyes by the end of next year.

Multiple challenges

One benefit of the current group of synthetic dyes used in the US — a group of reds, yellows, greens and blues — is their consistency. Manufacturers know how much of a dye to use in a given product, when to add it and how long it will last. In a large switch to natural dyes, these givens become unknowns.

Another unknown is availability. Natural ingredients — think elderberry, hibiscus, carrots, beets, cabbage, radishes and some botanicals and algae — need to be grown, which means the entire supply side will have to be reconfigured.

Since some natural ingredients are not sourced from the United States, the “administration’s trade policy and health and nutrition policy must be aligned to ensure both are achievable,” Andrew Jerome, vice president of communications for the International Dairy Foods Association, said.

The “administration’s trade policy and health and nutrition policy must be aligned to ensure both are achievable.” – Andrew Jerome, International Dairy Foods Association

Limited supplies for high-demand natural foods would benefit larger companies who can sign larger contracts, but smaller companies could struggle. It could take five years for most companies to hit the goals set by the FDA, including production of the colors and getting the crops in and harvested, Frame said.

“Where do we plant these so that we have enough of the material to make the colors especially when you concentrate them down?” Frame said. “And where in the world do they all grow … so where do you have to import these from?”

Also of concern are storage needs, such as refrigeration, which could increase food makers’ equipment needs.

“To have to have refrigeration to store colors can be a huge cost in itself,” Frame said. “And you may or may not have the facility space to even put refrigeration in. This is a much bigger ask than just ‘hey everybody let’s have this in place by 2026’ … there are too many pieces involved,” Frame said.

Synthetic dyes are much more stable than natural dyes, maintaining their colors much longer when exposed to heat, cold, light or acidity.

Anthocyanins — plant pigments found in berries, red cabbage, grapes and other fruits and vegetables — for example, create pinks in acidic foods and beverages but start to go purple or blue in more neutral products, like icing.

This potential color degradation could shorten shelf life for many products.

“Maybe before when you put it in the store and it would stay in the store a few months, and maybe now it only lasts a month,” said Monica Giusti, a food science researcher and associate chair and professor at Ohio State University’s Department of Food Science and Technology.

“Maybe you have to change the step in the process when you add the colorant. Maybe you were adding at the beginning, now you have to add later. That’s changing all of your protocols,” Giusti said.

And then there’s the finicky American consumer who likes soft drinks and snacks to appeal to their eyes as well as their taste buds.

Maraschino cherries, for example, are often artificially dyed to achieve a vibrant red color. Red radishes can be used instead, but “no one wants to eat maraschino cherries that taste like cooked radishes,” Giusti said.

Health benefits

Experts disagree on just how beneficial the changes will ultimately be for public health. Processed foods, regardless of the types of dyes used, are largely considered far less healthy than a diet of whole foods and grains.

“If children are consuming the kind of food that has dyes in it, the dyes are the least of their problems and a fraction of the issue compared to the sugar and fat in those products,” Shelke said.

But Giusti said that the changes effectively could get more fruits and vegetables onto people’s plates in the form of the natural dyes.

“This is an opportunity to incorporate more benefits from fruits and vegetables into a wide variety of foods that people are already used to consuming,” Giusti said.

Food industry associations pushed back on the suggestion current dyes used are harmful.

Melissa Hockstad, president and CEO of the Consumer Brands Association, said in a statement that synthetic dyes ”are rigorously studied” and “safe.”

“As we increase the use of alternative ingredients, food and beverage companies will not sacrifice science or the safety of our products,” she said.

(Featured photo by Helena Lopes for Unsplash+)