Climate change bringing challenges for Superfund site cleanup

By Barbara Reina

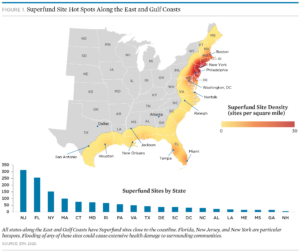

US efforts to clean up toxins and protect communities from some of the nation’s most contaminated sites are getting more difficult as climate change brings increasingly abnormal weather events that make containing chemical waste more challenging, experts warn.

Fast and heavy rainfall, sea level rise, sinking land and the loss of natural coastal barriers are among the factors that open the way for repeated flooding that can create havoc on US efforts to contain hazardous waste at many Superfund sites.

“There are hundreds of contaminated Superfund sites across the country that are at risk of extreme coastal flooding” and becoming “compromised,” said Jacob Carter, a scientist at the Partnership for Policy Integrity, who previously worked at the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). “I expect that we will continue to see more sites compromised as climate change progresses.”

Carter co-authored a 2020 report projecting at least 800 Superfund sites would be at risk of extreme flooding by 2040, even under a low sea level rise scenario.

Since then, the frequency and intensity of extreme precipitation has been on the rise, according to the 2023 US Government Fifth National Climate Assessment. In 2022 alone, the US experienced 18 weather and climate disasters with damages exceeding $1 billion.

A 2023 report published by the American Chemical Society adds to concerns, projecting more than 400 potential sites in California that deal with hazardous waste – though not necessarily Superfund sites – will be threatened by a 1-in-100 year flood event due to sea level rise by the end of the century if climate-altering greenhouse gas emissions continue unabated.

Washed away

One ongoing example of the challenges is seen in the Dewey Loeffel Landfill Superfund site in Rensselaer County, New York, where the EPA has been working for years to deal with hazardous waste that includes cancer-causing polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBS). Regulators estimate more than 46,000 tons of waste were dumped at the 19-acre site decades ago, triggering fish and animal deaths and uncontrolled fires. Contamination spread to groundwater, soil, sediment and surface waters, according to the EPA.

“The impacts of climate change and extreme weather events are an important consideration in the Superfund process,” said Joe Battipaglia, remedial project manager for the Dewey Loeffel Superfund site.

Part of addressing the contamination at Dewey Loeffel involves stabilizing Little Thunder Brook — a 1,900 foot tributary with high concentrations of PCBs embedded deep into the sediment due to runoff from the landfill. The EPA had excavated PCBs in the upper portion of the brook, and restored the waterway with clean soil and stone.

But an intense summer rainstorm in 2021 dropped 4.5 inches of rain in about 90 minutes, overwhelming and destroying much of the work. In August of this year, the EPA restarted permanent restoration work at the waterway, rebuilding the banks and creating barriers to withstand future high flow events. Another large storm hit last month, but so far the repair work appears to have survived without “significant impacts,” according to Battipaglia.

Potential climate-related impacts will be considered as part of the cleanup remedy selection process for the Dewey Loeffel Landfill site and during periodic reviews (every five years) of the site after the selected cleanup is completed, according to Battipaglia.

The Northeast US is seeing precipitation increase year round, and extreme precipitation events have increased “by about 60% in the region – the largest increase in the US” according to the 2023 climate assessment.

Heavy rainfall is expected to continue to plague the northeast, according to Jessica Spaccio, a climatologist with the Northeast Regional Climate Center.

Heavy rainfall is expected to continue to plague the northeast, according to Jessica Spaccio, a climatologist with the Northeast Regional Climate Center.

In New Jersey, the US state with the most Superfund sites, the America Cyanamid Superfund site has been continually impacted by flooding. In 2011, floodwaters from Hurricane Irene led to the release of benzene (a cancer-causing agent) outside the site.

Flood risk reduction measures were then put in place: the protective infrastructure was raised several feet above the flood high-water lines, a trench and treatment system was constructed with reinforcement of two berms for containment of chemicals at the site.

But flooding became a consistent problem for the New Jersey site, prompting an order by the EPA for the most expensive long-term remediation: complete removal of all contaminated soil at the site.

Wyeth Holdings LLC (Wyeth), a subsidiary of Pfizer Inc., purchased the New Jersey site in 2009 and assumed responsibility for its cleanup. The site’s long-term cleanup is ongoing.

Contamination of the Bridgewater, New Jersey site was caused by more than 90 years of waste from chemical and pharmaceutical manufacturing companies. Soil and groundwater were contaminated with various volatile organic compounds (VOCs), semi-volatile organic compounds (SVOCs), and metals.

In Houston, Texas, the San Jacinto River Waste Pits Superfund site was compromised by Hurricane Harvey in 2017. Nearby communities were at risk of exposure to dioxins — highly toxic chemical compounds that can cause reproductive and developmental problems, damage the immune system, interfere with hormones, and cause cancer.

Communities at Risk

Underserved communities living near these at-risk Superfund sites are particularly vulnerable to the effects of extreme flooding. “It’s a huge issue for people of color and low-income communities,” said Carter.

A Center for Science and Democracy Toxic Relationship Report states that between 2.3 and 14.5 million people of color living about five miles from an at-risk site could be affected by extreme flooding within the next 20 years.

“I don’t think the average person is aware of these Superfund sites, the extremely hazardous materials that they contain or the threats from climate change that exist,” said Carter.

A report from the Shriver Center on Poverty Law finds 70% of people living in assisted housing, live within one mile of a Superfund site.

“Poorer communities in areas that flood maybe can’t afford to move,” said Spaccio.

The Superfund program requires every Superfund site with dangerous levels of contamination to undergo a five-year review of ongoing cleanup plans regardless of whether or not flooding is a problem.

“The issue becomes more dire as time progresses,” Carter said.

(additional reporting by Carey Gillam)

(Featured photo by Barbara Reina.)

EWG

EWG