New EPA plan for hormone-harming pesticides sparks hope, but also skepticism

By Johnathan Hettinger

A new US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) plan aimed at protecting the public from exposure to pesticides that harm reproductive health is sparking hope for advocates who have called for action for more than two decades, but skepticism remains high.

The EPA is accepting public comments on the plan, which could impact regulation of several widely used pesticides, until December 26. But key players in the agrochemical industry – as well as some environmental advocates – are asking the EPA to extend the deadline, citing the complexity and magnitude of the EPA’s proposal.

The long overdue strategy comes after litigation and multiple Inspector General probes exposed decades of EPA inaction to deal with evidence that many widely used pesticides are disrupting human hormones in ways that interfere with healthy pregnancies and cause an array of other harms.

“Generally, we’re very happy EPA is finally taking some action on this program,” said Jenny Loda, a staff attorney at the Center for Food Safety (CFS). Last year, CFS sued the EPA on behalf of farmworkers for failing to abide by the Endocrine Disruptor Screening Program (EDSP) implemented by Congress as part of the Food Quality Protection Act of 1996.

Loda said that they will continue with their litigation, which has the potential to set court-ordered timelines on the EPA’s progress with the program.

“Politics, not science”

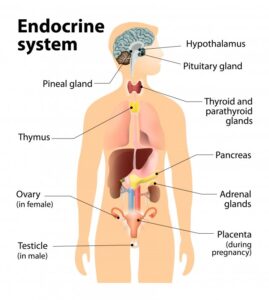

Under the law, the EPA is supposed to look at how pesticides impact the human endocrine system – the body’s hormonal system that controls or regulates many biological functions, including the functions of reproductive organs, growth, and energy levels. The agency is then supposed to incorporate that data and consider if restrictions are needed to protect the public from the risks.

Yet, for more than 25 years, the EPA has not determined even a single chemical to be an endocrine disruptor through its testing process, and has not put in a single regulation to protect consumers and farmworkers from pesticides that independent research has shown to be endocrine disrupting.

In fact, the agency has tested only 4% of all pesticides registered for endocrine-disrupting qualities and has not completed a second round of testing on any pesticides.

In 2011 and again in 2021, the EPA Office of the Inspector General (OIG) issued public reports detailing the EPA’s failure to take action on the EDSP. The 2021 Inspector General report found that the EPA was receiving $7.5 million a year for the EDSP program, but employees were told to operate as if it didn’t exist.

“That’s the story of the EDSP,” said Laura Vandenberg, a professor at the University of Massachusetts who has written about the program’s failures. “It’s underfunded, understaffed and the staff are told to basically work on something else. That sounds to me like politics, not science.”

In October – one year behind schedule – the Biden administration finally unveiled a non-binding strategic plan for how the EPA’s Office of Pesticide Programs would take up the EDSP.

“This plan is a major milestone in our efforts to ensure that pesticide decisions continue to protect human health,” Deputy Assistant Administrator for Pesticide Programs for the Office of Chemical Safety and Pollution Prevention Jake Li said in a statement at the time. “Starting with our highest priority chemicals, EPA will communicate more transparently our endocrine findings for humans, pulling from existing data when possible, and requesting new data when necessary to evaluate potential estrogen, androgen, and thyroid effects.”

Some pesticides can disrupt the endocrine system by blocking or mimicking the body’s hormones. People can be exposed through drinking water or eating food contaminated with pesticides and by breathing contaminated air. Farmworkers generally face higher risks of exposure than the general population because pesticides are widely used in agriculture. Even slight disruptions to the endocrine system can cause significant impacts on human health. Scientists have linked endocrine disruption to breast cancer, diabetes, obesity, infertility, and learning disabilities.

Scientists realized that diseases associated with endocrine disrupting chemicals were on the rise long ago, prompting the move by Congress in the 1990s to push the EPA to design a program to identify and deal with the public health threat.

The agency was initially supposed to implement the program by August 1999. After it missed its first deadline, the Natural Resources Defense Council, an international environmental nonprofit organization, sued the EPA, and since that time, the EPA has failed to implement the program, again and again missing court and self-imposed deadlines.

Despite the decades of delay, companies that sell widely used pesticides, including herbicide makers Syngenta and Bayer, which bought Monsanto in 2018, are asking the EPA to further delay implementation of its plan. Both companies, along with agrochemical industry lobbyist CropLife America, have asked the EPA to extend the public comment period 90 days.

“Bayer has a large number of technical active ingredients that need to be assessed to determine if there is other scientifically relevant information available to provide to the

Agency,” Bayer said in a letter submitted to the EPA last month. Bayer’s glyphosate-based weed killing products – inherited from Monsanto – are currently under global scrutiny as many scientists point to what they say is evidence of a range of human health risks from glyphosate exposure, including endocrine disruption.

And, calling the plan an “important step,” the Environmental Protection Network, which is a group of former EPA staffers, has asked the agency to extend the public comment period for 30 days to “allow the public the time needed to prepare the most comprehensive comments possible.”

“Lost faith”

Under its new plan, the EPA says it will prioritize understanding the effects certain pesticides have on human endocrine systems, while delaying looking into wildlife effects. The agency said it will use existing data it already has, phasing in requirements for new research data over time as pesticides come up for registration review. Under the law, pesticides are supposed to be reviewed for safety every 15 years.

Currently, the EPA has two tiers of testing required to determine if a chemical is an endocrine disruptor. First, pesticides go through Tier 1 testing to determine whether it has the potential to be an endocrine disruptor. If a chemical is determined to have that potential, it’s supposed to move on to Tier 2 testing, which makes a determination.

However, the EPA has never had a chemical go through Tier 2 testing, despite having some chemicals test as potential endocrine disruptors.

Maricel Maffini, an independent consultant who has researched the EDSP, said that there is a lot of research that shows particular pesticides, such as atrazine, chlorpyrifos and glyphosate, are endocrine disrupting chemicals, but the EPA has refused to incorporate a lot of peer reviewed literature on these pesticides.

“How many positive tests do they have to have to call a black cat a black cat? They have never come to terms with having to make decisions. They have been kicking the can down the road,” Maffini said.

The EPA has lost a lot of public trust during this delay, according to Jennifer Sass, senior scientist at the Natural Resources Defense Council.

“People have lost faith in EPA to do this work,” said Sass. “They’re bending over backwards to not call things harmful that everyone knows is harmful.”

EWG

EWG