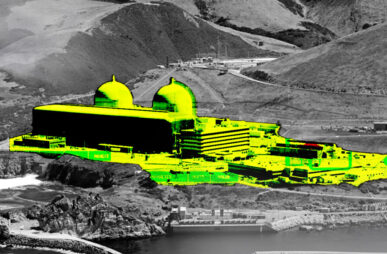

Postcard from California: Carbon capture won’t solve climate crisis

Four miles from my house, a Silicon Valley company wants to drill an 8,000-foot-deep well to store millions of tons of carbon dioxide (CO2), the greenhouse gas identified as the main cause of the climate crisis.