Microplastics drive plaque buildup in arteries of male mice, study suggests

Listen to the audio version of this article (generated by AI).

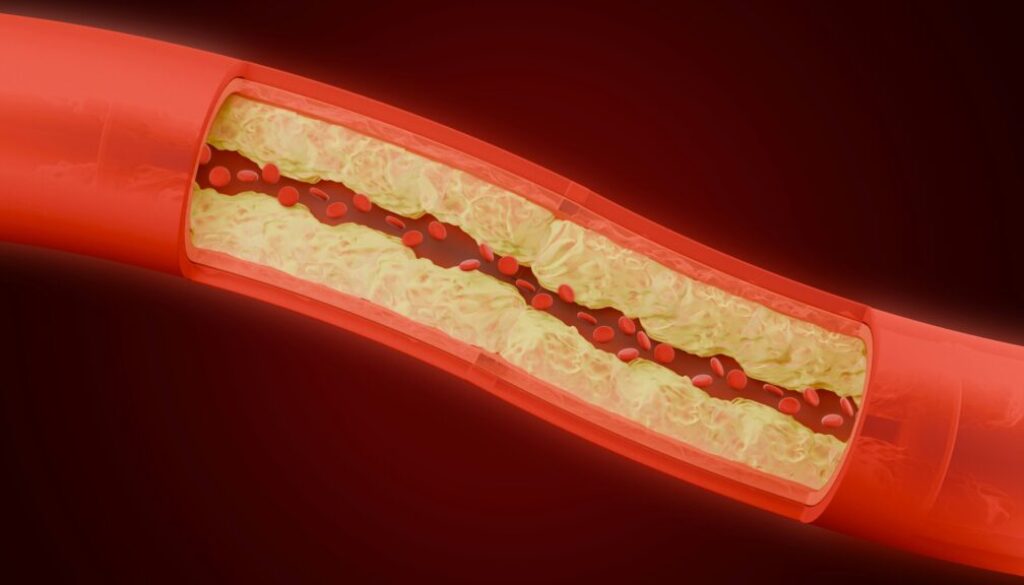

Exposure to tiny plastic particles that litter the environment may speed plaque buildup in the arteries of male mice, a condition that leads to heart disease, according to a new study.

The study, published Nov. 17 in the journal Environment International, found significant increases in plaque buildup in the arteries of male mice exposed to bits of plastic less than 5 millimeters long, called microplastics, at doses similar to what they would encounter in the environment.

The researchers said they also found changes in related cell types and activated genes linked to plaque buildup, although the mice did not develop obesity or high cholesterol, which are tied to the condition.

Female mice were not similarly impacted. Estrogen may have had a protective effect in the study’s female mice, sparing their arteries from microplastics-driven plaque buildup, the authors suggested.

“This study emphasizes the importance of limiting human exposure to sources of microplastics and of implementing approaches to limit their production,” said Timothy O’Toole, an associate professor of medicine at the University of Louisville who was not involved in the study.

Microplastics are shed from numerous everyday products, including clothing, packaging and plastic items, contaminating food, water and air globally in what experts call a plastic pollution crisis. Representatives from countries around the world gathered in Geneva, Switzerland in August to discuss for the sixth time a treaty to combat the crisis, but failed to come to an agreement.

The new study adds to a growing body of alarming research that shows microplastics are accumulating in the brain, lungs, kidneys, joints, blood vessels and other human body parts. The findings come on the heels of a Nov. 6 report that found human health impacts associated with the use of plastics in the US may total $930 billion, and a separate August report warning that plastics are responsible for about $1.5 trillion annual health-related costs worldwide

The new findings also help clarify the role microplastics play in heart disease, suggesting they are directly involved in the initiation or progression of plaque buildup, said O’Toole. “While the presence of microplastics of various types have been identified in blood vessels and diseased hearts, and the levels of these microplastics have been associated with severity of disease and likelihood of future adverse outcomes, their direct involvement in cardiovascular disease has been uncertain,” he said.

A study by O’Toole and his team, published April 2024 in the journal Circulation Research, found that male mice given water tainted with polystyrene, a widely used plastic, had higher fat buildup in their heart valves after 20 weeks than male mice given normal water to drink (the study did not assess female mice).

The findings from both studies address “justifiable questions” raised in a March 2024 New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) paper “about whether microplastics cause the disease or were just bystanders,” said Matthew Campen, a health sciences researcher at the University of New Mexico and an author of the Environment International study.

The NEJM study compared health outcomes in over 250 patients with or without microplastics and even smaller particles called nanoplastics in their arteries. They found that patients with carotid artery plaque containing the plastic particles had a higher risk of heart attack, stroke or death from any cause after an almost three-year follow-up than those in which the particles were not detected.

“It is important to note that our results do not prove causality,” the authors of the NEJM study wrote, noting that the findings could be impacted by risk from other types of exposures during a patient’s life, as well as their health status and behaviors.

Featured image: Zyanya Citlalli via Unsplash.