Paraquat imports climb despite concerns about health impacts

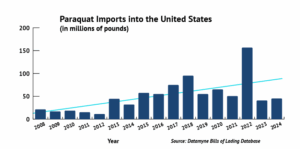

The US has been importing increasing amounts of paraquat, a pesticide widely used in farming that is linked to Parkinson’s disease, even as other countries have banned the chemical amid growing concerns about risks to human and environmental health, according to the findings of a new report.

Over a recent eight-year period, US imports of paraquat have totaled between 40 million and 156 million pounds per year, most coming from China and Chinese-owned manufacturing operations in the United Kingdom, the report states, citing import records. China announced in 2012 it was phasing out the use of paraquat and a ban in the UK took effect as part of a broad European Union paraquat ban in 2007. Dozens of other countries have also banned paraquat.

On average, paraquat imports have been on the rise since 2008, with a large spike seen in 2022, according to the report, which is a product of the Pesticide Action & Agroecology Network (PAN) and Coming Clean, both environmental health advocacy groups, and Alianza Nacional de Campesinas, an advocacy group for women farmworkers.

The report cites multiple Chinese factories as supplying paraquat to the US in recent years but singles out Sinochem Holdings, a Chinese government-owned company and parent to paraquat maker Syngenta, as among the key suppliers by way of a Syngenta manufacturing facility in central England.

Sales in the US are “helping to prop up demand for a toxic product with a shrinking global market,” the report states.

“The health and environmental harms of paraquat will be felt in US communities for generations – while the profits from paraquat sales largely flow outside the US, to a foreign-owned mega conglomerate,” the report states.

The groups behind the report advocate for banning paraquat and providing incentives for farmers to avoid use of all synthetic pesticides. They say paraquat is emblematic of broad problems across the pesticide industry.

“I hope this research shows that giant, foreign-owned companies are the ones profiting from weak US pesticide regulations,” said Deidre Nelms, spokeswoman for Coming Clean and author of Tuesday’s report.

“These companies can’t be trusted to solve the health and environmental problems they had a hand in creating in the first place,” she said. “Farming without pesticides is the only viable way to protect the health of the people who grow and harvest our food.”

A Syngenta spokesperson said it is one of more than 750 companies around the world that are registered to sell paraquat, and the pesticide accounts for only about 1% of the company’s crop protection product sales globally and even less in terms of profitability.

“It’s place in our innovation-focused portfolio reflects primarily our commitment to farmers who value paraquat for its effectiveness in protecting agriculturally important crops such as soy, corn and rice against invasive weeds,” the company spokesperson said.

Specific concerns

Specific concerns

The report points to specific concerns about disproportionate harm to Latine and low-income communities, citing a study of more than 800 Parkinson’s disease patients in California’s Central Valley. That report found that living within 500 meters of a paraquat application site over a prolonged period was associated with a 91% increase in the odds of developing Parkinson’s disease.

The report additionally states that every stage of the paraquat supply chain emits harmful greenhouse gases and toxic air pollutants. SinoChem’s paraquat supply chain includes fossil fuel extraction in Equatorial Guinea and Saudi Arabia, as well as chemical manufacturing in India, Germany and the UK, with final formulation and distribution in the United States, according to the report.

The report found a Syngenta facility in St. Gabriel, Louisiana, which formulates and packages the paraquat-based Gramoxone brand among other products, released over 52,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide in 2023, according to data from the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and has sent more than 49,000 pounds of paraquat waste product to incinerators, an underground injection well and a toxic waste landfill over the last decade.

“Each stage of the Gramoxone supply chain, which spans four continents, causes toxic and climate-warming pollution,” the report states. “And only one powerful company profits.”

The Syngenta spokesperson said the paraquat waste totals were not unusual for the industry.

“We typically ship out only a few thousand pounds of paraquat-related waste for disposal each year,” the company spokesperson said. “The carbon footprint of Paraquat production is not dissimilar to other chemical active ingredients.”

Sinochem did not respond to a request for comment.

US trade policy under the Trump administration has encouraged continued imports of paraquat, the report notes, citing the administration’s exemption of paraquat (among other agricultural products) from tariffs imposed in April on Chinese imports. And in May, the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) rescinded a requirement that US farmers keep records of all their use of paraquat and certain other pesticides.

A “highly toxic pesticide”

In the US, paraquat is not sold for residential use and is only allowed for use by professional applicators. It is widely used by farmers to kill weeds in their fields, and to dry out crops for harvest. It is used in orchards, wheat fields, pastures where livestock graze, cotton fields and elsewhere. As weeds have become more resistant to the top-selling glyphosate herbicide, paraquat popularity with farmers has surged.

The US Geological Survey (USGS), which last published data on annual agricultural paraquat use in 2018, estimates that more than 17 million pounds of paraquat was applied that year on farmland, more than double the amount applied in 2008.

Despite its widespread use, the pesticide has become the subject of a nationwide public health and policy debate with many lawmakers and health advocates calling for state and federal bans on paraquat use.

A chief concern is scientific research dating back decades that links long-term paraquat exposure to disease, primarily the incurable brain disease known as Parkinson’s.

Last year, more than 50 US lawmakers called on the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to ban paraquat, calling it a “highly toxic pesticide” whose continued use cannot be justified givens its harms to farmworkers and rural communities.”

The lawmakers cited “numerous studies” that have found paraquat causes serious health risks that include a high risk of developing Parkinson’s disease, as well as risks of non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma, thyroid cancer, and other issues.

The Michael J Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research has also urged a ban, providing the EPA with “a strong body of evidence” linking paraquat to Parkinson’s, including indications that paraquat may increase Parkinson’s risk by 100-500%.

A 2022 Parkinson’s Foundation-led study found that nearly 90,000 people are diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease every year in the US.

Thousands of pending lawsuits

Syngenta has repeatedly denied there is any valid connection between Parkinson’s and paraquat.

But internal Syngenta documents revealed by The New Lede in a reporting project with The Guardian show the company was aware many years ago of scientific evidence that paraquat could impact the brain in ways that cause Parkinson’s, and that it employed many tactics to downplay and discredit that evidence and protect paraquat profits.

More than 8,000 people are currently suing Syngenta, alleging they or their loved ones developed Parkinson’s from paraquat exposure, and asserting that instead of warning of the risk of the incurable brain disease, Syngenta instead worked to hide the evidence of risk.

Syngenta is currently working to finalize a sweeping settlement agreement with some plaintiffs’ attorneys in hopes of ending the litigation, though some plaintiffs’ attorneys oppose the deal and say it is deeply flawed.

The EPA states on its website that after reviewing the science, it has “not found a clear link” between paraquat exposure and Parkinson’s disease, though the agency does have a number of restrictions on use of the chemical due to its acute toxicity. The EPA, which was sued in 2021 by farmworkers and environmental groups over its re-approval of paraquat, had said it would issue an updated final report on paraquat in January 2025 but then said it needed more time.

The agency then said in a July court filing that it would be obtaining a study of paraquat volatilization to determine “the potential inhalation risks of paraquat for people who are not involved in the pesticide application.”

Featured photo is of transportation cargo containers. (Credit: Media handout from Syngenta Group)