Trump – Making America Polluted Again

President Donald Trump’s campaign to carve up federal environmental agencies and paralyze statutes that cleared the air, cleaned US waters, and protected wildlands marks the opening of MAPA, the new era to Make America Polluted Again.

With uncanny speed and premeditated precision, Trump and his cabinet are cutting budgets, slicing protections from statutes, and pushing thousands of seasoned scientists and resource managers out of the federal government’s principal environmental agencies: the Environmental Protection Agency, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, US Geological Survey, the US Department of Agriculture, and the Department of the Interior.

Because the ecological systems at risk are dynamic, the consequences – reappearance of smog in cities, dirtier lakes and rivers, vast fish kills, more human disease – will take years to become fully manifest, which is the primary reason that MAPA has attracted remarkably scant resistance.

That needs to change, and fast. A powerful example of just how contaminated and dangerous MAPA will be is already evident in Iowa. Years of poor stewardship, weak enforcement, and political intimidation have yielded grievously contaminated water statewide from pesticides, fertilizer, and hog, cattle, and chicken manure that fouls creeks and lakes. The mess puts the health of every Iowan in peril – and extends that peril more than 1,200 miles downstream to the Gulf of Mexico. That’s no exaggeration.

Many of Iowa rivers monitored for water quality have formally been declared as impaired, meaning they are so polluted no new discharges from any industrial source is permitted. Most of Iowa’s recreational lakes develop toxic algal blooms every summer, making them unfit for swimming. In recent years, Iowa citizens have developed the second-highest incidence of cancer among all states, and the state has the fastest-rising rates, according to a 2024 state cancer report.

This summer another ecological shock rocked Iowa when the water authority in Des Moines, the state capital, issued the first mandatory restrictions on water use in its history. The limits came in response to concentrations of nitrates that were more than twice the US safety standard – and the highest since 2013 – in the two rivers that are the sources of drinking water for 600,000 residents.

Almost all of Iowa’s pollution from nitrates – a suspected carcinogen – come from fertilizer spread on farm fields and manure from Iowa’s industrialized hog, cattle, and poultry operations. Iowa agriculture discharges more of both into its waters than any other state.

Keep in mind that Iowa’s citizens and government authorities, like those in every other state, once valued the statutes and agencies that scrubbed the skies, cleared the waters, cleaned up toxic dumps, secured wildlife habitat, and implemented countless other steps to manage their environment. Older Iowans recall clean streams and lakes for fishing and swimming.

How Iowa developed its worst-in-the-nation-water quality is a story of mounting MAPA-like neglect. Decades of political influence exerted by Iowa’s agriculture sector convinced state and local governments, academia, business associations and rural residents that farm production and steadily climbing revenues took precedence over the safety of state waters and the health of Iowa’s more than 3 million residents.

What Trump is pursuing now, just like Iowa did starting in the early years of the century, is a perilously different course in how America manages its natural resources. Trump explained the rationale in a statement in April, stating that “outdated regulations” were a “drag on progress.” By rescinding regulations, the statement said, “we can stimulate innovation and deliver prosperity to everyday Americans.”

That’s essentially the logic that over time led to Iowa’s wretched water. Some 30 million of Iowa’s 36 million acres is farmland. Until the late 1970s and 1980s Iowa agriculture encompassed nearly 134,000 farms, most of them much less ecologically damaging 300-acre to 400-acre mixed crop operations with manageable herds of hogs and dairy cows raised in pastures.

Today there are almost 50,000 fewer farms in Iowa. They are much larger, more specialized, more productive, and spread more fertilizer on crops than farms in any other state. Most that raise livestock and poultry keep their animals indoors in mammoth feeding and milking operations that produce roughly 100 billion pounds of raw manure annually.

The transition from smaller producers to industrial-size crop and animal production yielded more corn, soybeans, pork, cattle, and poultry. It also produced a torrent of nitrates and phosphorus that Iowa residents grew modestly concerned about in the century’s first decade when harmful algal blooms began forming in state lakes.

In 2013, the state experienced its first farm nutrient pollution crisis when nitrate levels in the Raccoon River, one of Des Moines’s drinking water sources, reached 24.39 parts per million, more than twice the federal safety standard of 10 ppm.

The presence of such high nitrate levels produced a pulse of activity by important players in Iowa.

The water authority, Des Moines Water Works, managed to bring nitrate levels in drinking water back under the safety limit by blending Raccoon River water with clean water from its other sources.

The State Legislature approved the Iowa Nutrient Reduction Strategy, led by Iowa State University, to convince and compensate farmers for embracing voluntary pollution prevention practices like not plowing their fields, and planting soil-protecting cover crops and buffers along streams to absorb fertilizer and manure.

In 2015, with state funding, Iowa State and the University of Iowa hired Chris Jones, a chemist, to expand the state’s water-quality monitoring network from 12 monitoring stations to 70.

Also In 2015 Des Moines Water Works sued drainage districts in three upstream counties to halt farms from discharging nutrients into the Raccoon.

As it turned out, none of these steps had any influence on the escalating levels of nitrates and other farm pollutants that drain into state waters.

A federal district judge dismissed the Water Works lawsuit in 2017.

From his perch as director of Iowa’s water quality monitoring, Jones confirmed that the state nutrient reduction strategy had no effect on farm nutrient discharges to state waters. In one year, a billion pounds of nitrates flowed off Iowa farmland into the Mississippi River, and became the primary cause of the low-oxygen “dead zone” in the Gulf of Mexico.

In 2023, Iowa health authorities startled residents when they reported the state’s second-in-the-nation cancer incidence.

How has Iowa responded to mounting evidence of contamination and cancer? With a MAPA-like back of the hand that has been accepted by most state residents. Even as pollution grew worse the governor’s office, legislature, and local governments got politically redder.

It’s resulted in some harrowing events. Before it was killed earlier this year, the legislature spent two years giving serious consideration to a proposal to help protect chemical companies from lawsuits brought by residents who allege their health has been damaged by exposure to their products.

Jones was pushed out of his job in 2023 by influential Republican state senators closely connected to agriculture, and the number of water-quality monitoring stations statewide will be cut to 20 in 2026. In 2024, even Iowa’s cancer research group blamed the state’s rising incidence of malignancies on “binge drinking.”

By opening a new era to make America polluted again, Trump is turning aside half a century of accomplishment on protecting natural resources and public health. The rocket rise of cancer and the diminished condition of Iowa’s water and land are deadly warnings. Unless there is powerful public pushback, what’s happened in Iowa will occur in all other states.

Opinion columns published in The New Lede represent the views of the individual(s) authoring the columns and not necessarily the perspectives of TNL editors.

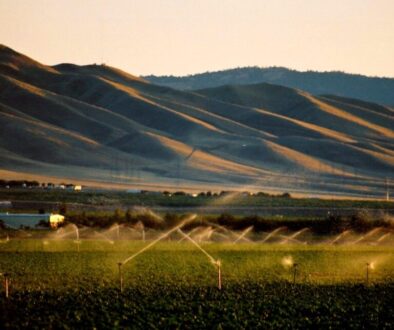

(Featured photo by Getty Images for Unsplash +.)