The unseen harvest: Pesticides, cancer and rural Missouri’s health crisis

(This article is republished from Investigate Midwest.)

By , , and

KENNETT, MO. — Nestled in Missouri’s Bootheel is the small town of Kennett, the Dunklin County seat. With just over 10,000 residents, it’s a close-knit community where good-natured teasing is a common show of affection.

Once a sprawling swampland, it has since been transformed into an expanse of flat, fertile fields where agriculture stands as the backbone of the region’s economy.

Kennett’s houses don’t get much taller than one story, and as visitors stroll down the main street, they’re welcomed by a mix of restaurants, boutiques and a cozy hair salon. These buildings are dwarfed in size by a silent, boarded-up hospital, its vacancy a remembrance of what the community has lost.

It’s the kind of community where if something tragic happens, everyone finds out.

Bobbi Bibbs found this out the hard way. She discovered she had cancer in her colon in December 2023, which then metastasized to her liver, making it a stage four diagnosis.

Bibbs isn’t alone. Dunklin County is among the 10 counties with the highest rates of that type of cancer in the state. This isn’t just a statistic, Bibbs said she can see it and almost can’t fathom it.

“There are so many (cases) where we are from,” Bibbs said. “Like, it’s got to be coming from somewhere.”

Bibbs is surrounded by people who understand her struggles, many of whom work in the agriculture industry. In Dunklin County, there are hundreds of thousands of acres of crops — and most of that land is blanketed by pesticides.

Estimates suggest that thousands of kilograms of pesticides are sprayed over Missouri cropland each year. In some places, wastewater sludge containing “forever chemicals” — per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances — is applied on farmland as fertilizer.

Multiple scientific studies have explored a connection between pesticide use and cancer, pointing to a silent public health crisis hitting rural communities particularly hard.

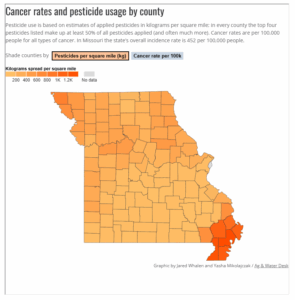

The University of Missouri (MU), in partnership with Investigate Midwest, conducted a county-by-county analysis of cancer rates and pesticide use, using the most recently available data for pesticides that are repeatedly cited in research as likely to be associated with cancer risk.

The six counties with the highest use of these pesticides per square mile are all located in the Bootheel, including Dunklin. Four of those counties are in the top 15 for overall cancer rates in Missouri. All counties with the highest rates of cancer are rural.

The six counties with the highest use of these pesticides per square mile are all located in the Bootheel, including Dunklin. Four of those counties are in the top 15 for overall cancer rates in Missouri. All counties with the highest rates of cancer are rural.

So in Kennett, there are high rates of chemical usage, high rates of cancer — and the nearest trauma center in the state is more than an hour and a half away.

In other words, it’s a typical rural town in Missouri.

Green hills and kilograms of chemicals

While Missouri has its share of rolling hills covered in trees and wild foliage, much of the land is well developed to suit the needs of farmers and their crops. There are about 27 million acres of Missouri farmland being cultivated and nearly 88,000 farms, according to the Rural Farm & Finance Policy Analysis Center.

The biggest business in the state is agriculture, employing about 460,000 statewide, according to the Missouri Department of Agriculture. Soybeans, corn and wheat are some of the crops that color most of the state’s landscape.

Farming is a dangerous job that requires a good deal of heavy equipment and specialized tools. Those tools include chemicals.

Isain Zapata is a data scientist who researched the relationship between pesticides and the incidence of cancer. He looked at the complex mixtures of pesticides tailored to specific crops that are sprayed in different regions.

“When we look at those pesticides, it’s not just one — it’s all a cocktail,” Zapata said. “It’s the whole rainbow of different colors.”

He found that these colorful combinations are strongly linked to certain cancer rates across the nation.

“Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and leukemias are very intimately associated with pesticide use,” Zapata said. “But we also saw that the overall pesticide use has an effect on all the other non-obvious cancers.”

Other research shows an association between certain pesticides and an increased risk of brain, prostate, breast, kidney and colon cancers.

Pesticides are a classification of substances used to protect crops. This includes killing weeds, insects or even strengthening wood to prevent pests from harming the plant. Farmers typically apply pesticides to crops using methods such as aerial spraying or ground-based equipment.

Serious risks are posed by pesticides because they can harm both human health and the environment. Exposure may lead to short-term or long-term health problems, while also contaminating soil and water, which may disrupt ecosystems and affect wildlife.

But pesticides do what they do best. Zapata emphasizes that without pesticides, agriculture-based economies and the communities tied to them would suffer.

“I am not in favor or against pesticides,” Zapata said. “I know we need them. I don’t like them, but I know why they have to be there.”

He said rural agricultural areas are home to an intense combination of factors that multiply the risk level.

Farmers are under pressure to maintain or increase their productivity, and that comes at the cost of using compounds that carry health risks, Zapata said. Rural areas are often underserved by health care facilities, meaning there are often too few health providers and resources in those areas to monitor and manage the added risk of using pesticides.

“It’s just the perfect storm,” Zapata said. “You combine several factors (heavy pesticide usage, poor regulation and monitoring, socioeconomic disparities), you’ve made it worse.”

The million-acre highway

Mike Milam is a local expert in pesticide application. Based in Kennett, he is a field specialist in agriculture and environment for MU Extension, serving Dunklin, New Madrid and Pemiscot counties.

“I’ve had people tell me, especially the ones who don’t like chemicals at all (that) our bodies weren’t designed to breathe these chemicals,” Milam said. “And they’re right about that.”

The herbicide Roundup is the target of thousands of lawsuits claiming it causes cancer, putting it in the spotlight. Milam listed other chemicals that have caused concern, including paraquat, vydate and dicamba.

Farmers and the workers hired to harvest crops frequently interact with chemicals. From mixing to pouring to spraying, they are there for all of it. They also encounter other farmers’ chemicals when a substance sprayed in one area drifts somewhere it was not intended to be.

“I have known a situation (where) people out in the fields got sprayed, or they sprayed next to them, and then it drifted over. And things like that,” Milam said. “Matter of fact, when I was in graduate school, I was in a field down in Louisiana, and they were spraying right next to us. We actually had to leave the field.”

Direct drift occurs when an applicator applies a pesticide and the wind blows it elsewhere, making monitoring weather conditions an integral part of the process. The stronger the wind, the stronger the potential is for drift.

That said, farmers have a limited window to seed and fertilize their fields during planting season. Fluctuating weather conditions can make this even more difficult. This spring alone, the Bootheel faced tornadoes, dust storms and historic flooding, all of which have the potential to hinder field work.

“We go out here, we can plant a crop, it looks beautiful, a flood wipes it out, and we gotta start back over,” said Sen. Jason Bean, R-Holcomb, a fifth-generation Bootheel farmer.

Milam said that some farmers end up spraying their crops when conditions aren’t ideal.

“The farmers aren’t paying attention or just decide to go ahead and (apply) anyway because they need to get it done,” Milam said. “They are under a lot of stress, they’re trying to get the crops in.”

Jason Mayer, a fourth-generation Bootheel farmer and one of the directors for the Missouri Soybean Association, believes that, nine times out of 10, farmers are doing the right thing. In his mind, it is the “bad actors” going against best practices. Bean compares this to speeding on the highway.

In his analogy, like drivers on the road minding the speed limit, most farmers follow the rules. Just as there will always be that driver blowing past everyone else in the left lane, there will be farmers who break the rules.

Agricultural regulators — such as the Missouri Department of Agriculture or EPA — serve as the cop on the side of the road in the metaphor. They step in when misuse is suspected. Environmental Protection Agency inspectors can show up at any time and ask to see a farmer’s records, Milam said.

With millions of acres of farmland in Missouri, that’s one big highway to watch. So if agencies don’t catch someone breaking the rules, it can fall to local farmers to report their neighbors to the state pesticide control office.

Bean emphasized that proper pesticide application isn’t just about compliance, it’s also in the farmer’s best interest. Misuse wastes costly chemicals, reduces crop effectiveness and decreases consumer trust in locally grown produce.

“I’d say we’re great stewards of the land,” Bean said. “We’re going to continue that, because in the big picture, farmers want to produce for the world the safest, abundant product.”

Milam said the key is to use the chemicals appropriately to minimize exposure. He said wearing personal protective equipment during application is a best practice. So doing things like wearing long pants, long-sleeved shirts, masks and goggles is essential for safe use.

Bean does not believe pesticides cause or increase the risk of cancer. Mayer echoes this sentiment, emphasizing his lifelong experience around crops and chemical applications.

“I’m 42 — knock on wood — today,” Mayer said. “I’m still relatively young, perfectly healthy, and I’ve been on the farm since I was 14.”

Waiting on a waiting room

Striking up a conversation about health care in Kennett is bound to lead to one topic: the hospital.

Kennett doesn’t have one anymore; Twin Rivers Regional Medical Center closed its doors in 2018.

For quick stitch-ups or infection treatment, St. Bernards Urgent Care is open every day. It closes at 7:30 p.m., meaning that Kennett residents have to go elsewhere for their nighttime care.

There are various options in nearby counties, or even in neighboring states, but if someone needs emergency care, for example, it’s a trek.

While there’s a Mercy Hospital located in nearby Dexter with a rotation of specialty doctors, the closest Missouri trauma center to Kennett is in Cape Girardeau, about an hour and a half away.

“(If) I have a heart attack at eight o’clock at night, or stroke, and if (the urgent care) was still open, they could give me that little fancy pill and help get me to the hospital to help,” said Cheryl Bruce, the executive director of the Dunklin/Stoddard Caring Council, an organization based in Kennett offering an assistive services program to Dunklin County residents with cancer.

Kennett’s old hospital building is still standing on the town’s main drag. The windows are boarded up, and walking through the halls requires ducking wires and tiptoeing over glass shards.

The current owner is in a zoning battle to turn the hospital into something. They haven’t been able to find buyers yet because they need various approvals from the city to do any work to make the building sellable.

Kennett isn’t alone in facing minimal health care access. Since 2014, 21 hospitals have shut down statewide, including 12 in rural areas, according to the Missouri Hospital Association.

Additionally, the Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform’s 2023-2024 report found 26 rural hospitals in Missouri are at risk of closure due to financial strain — nine of them are at an “immediate risk.”

The Twin Rivers CEO said in a 2018 statement that the hospital’s closure was part of an effort to consolidate operations with Poplar Bluff Regional Medical Center, “as health care delivery evolves and medical innovation makes inpatient services less needed,.” KFVS12 TV reported at the time.

It was a palpable loss for Kennett — people miss the hospital, Bruce said.

“When the hospital closed, all anybody has ever talked about is, ‘Are we going to get another one?’ ” Bruce said.

From 2020 to 2024, the Caring Council’s cancer assistive services program spent $22,650 helping over 400 people with transportation. For cancer care, folks in Kennett often travel an hour to Jonesboro, Arkansas, or an hour-and-a-half to Cape Girardeau in Missouri. Whatever kind of cancer care you need,, Bruce said, you’ve got to drive to get it.

The lack of health care providers also means early detection of medical issues, including cancer, can be harder to get.

Some health care transportation programs are available in rural areas, but Bruce said she sees a need in her community for more robust services.

“I’m not asking for a bus system like in St. Louis or Kansas City or Jeff City,” Bruce said. “I’m just asking for access to care, whatever that means.”

Sprayed on all sides

Wherever you go in Kennett, there will be someone who’s called it home their whole life. Kennett’s City Clerk Jan McElwrath is one of those people. Aside from a brief stint at the University of Missouri, she’s spent nearly all of her 68 years in town.

She came back for a classic reason: love. She got married, raised a family and built a life rooted in the same streets where she grew up.

Over the decades, she’s seen businesses open and close, celebrated countless community milestones and weathered natural disasters. Through it all, McElwrath has observed one constant: despite differing beliefs and opinions, the people of Kennett always find a way to come together.

“Our strength is our people, hands down,” she said.

This is especially important when considering the unique challenges of rural living.

An index created by the CDC shows that Dunklin is the county in Missouri least prepared to deal with economic or environmental challenges. According to Feeding America, over 20% of Dunklin County is food insecure, despite the fact that the region is covered in farmland. Milam said that this is largely because the farms in Dunklin are agronomic, which is when crops aren’t always grown for direct human consumption.

“It would help a lot of people if they had fresh vegetables,” he explained.

As manufacturing jobs moved out of many places in the Bootheel, Kennett felt the economic sting. Though Cim-Tek Filtration’s arrival two years ago brought back some manufacturing jobs, Kennett lost its Emerson Motor Company plant in 2006.

One industry that remains is agriculture.

The land is dotted with cotton, soybean and rice row crop operations. McElwrath calls the rows of cotton ready for picking “southern snow,” but to get that snow, farmers usually have to give plants a nudge with defoliants.

Defoliation is a natural process, though it can be artificially induced when chemicals are applied to the plants to get them to open up, making the white cotton easier to harvest.

McElwrath said it’s hard to notice farmers defoliating at first. But then, suddenly, your sinuses sting, your eyes burn, maybe a headache creeps in. It always seems to hit around the same time every year, right when the county fair is going on — with the dust, the dry soil, the demolition derby — everything blending together.

It’s not just that the defoliants make things happen quicker; they help make the cotton a higher grade — that means there is less debris affecting the final product. The grade determines the value.

Many residents of Kennett recognize the need for defoliants and other agricultural chemicals. For some of them, that’s what puts food on the table. But then the time of year creeps around again, and they all experience that familiar sensation.

“We’re surrounded by agriculture,” McElwrath said. “We recognize (chemicals) as a risk, but our economy here is very dependent on agriculture.”

(This article is part of a series produced by students at the University of Missouri School of Journalism.)

(Featured photo by David Ballew on Unsplash.)

August 25, 2025 @ 2:52 pm

This article seems to convey/draw the conclusion that residents in this area of Missouri along with the agricultural “experts: are simply willing to accept the health risks (including increased risks of cancer) of conventional agriculture, rather than to consider/convert to safer, less harmful practices.

Or did I miss something?

August 26, 2025 @ 3:16 pm

Yes that is what I got out of it too and that they are trying to convince us all that the products they are producing are safe to use & consume. When we & they know its all a bunch of lies. End goal eliminate the majority of humanity.