Outrage in Iowa – Residents demand action to clean up dangerously polluted water

Listen to the audio version of this article (generated by AI).

DES MOINES, Iowa — Several hundred Iowa residents gathered in the state capital this week, calling on public officials – and each other – to take swift action against dangerously polluted water supplies that are closely linked to the state’s powerful agricultural industry.

Some attendees drove for hours from rural farmsteads for the Aug. 4 event, squeezing into a packed auditorium on the campus of Drake University to listen to a team of scientists detail new research showing how multiple harmful pollutants flowing through Iowa watersheds are jeopardizing public and environmental health.

The crowd cheered and applauded loudly as speakers outlined a need for new regulations on farm pollution, while discussion of moves by public officials to slash funding for water quality monitoring devices drew a chorus of boos. Organizers counted more than 600 attending in person and said more than 230 participated online.

The forum focused on data in the research report, which was commissioned by Polk County officials in Des Moines and released by county commissioners last month. It adds to years of mounting evidence that pesticides, fertilizers, manure and other contaminants from Iowa farms and livestock operations are contaminating waterways used for drinking water, fishing and swimming, and likely contributing to the rising cancer rates that are impacting families across the state.

“Where do we want the state to be in 25 or 50 years?” Larry Weber, a University of Iowa scientist who helped author the water report, asked the audience. “When are we going to start to make the choices that put us in a position that moves us in the right direction?”

Seeking a “course correction”

Iowa has the second-highest rate of cancer in the nation, and has become one of only two US states where cancer overall is increasing. Leukemia, as well as cancers of the pancreas, breast, stomach, kidney, thyroid and uterus, are among the different cancer types on the rise across Iowa, according to the National Cancer Institute.

Many of the chemicals and other pollutants contaminating water sources are scientifically linked to these cancers as well as other health problems.

“Where do we want the state to be in 25 or 50 years?” – Larry Weber, University of Iowa

Nitrates, generated by fertilizer and manure, are a particular concern, routinely found in Iowa waters at levels above the 10 milligrams per liter federal regulators set as a safe standard. Babies are at risk for severe health problems when consuming nitrates in drinking water, and exposure to elevated levels of nitrates in drinking water has been linked by researchers to cancers of the blood, brain, breast, bladder, and ovaries.

Nitrate levels this summer in Iowa have been so far above federal standards that the utility serving 600,000 people in and around Des Moines restricted water use because the utility could not safely clear the high levels.

Though the restrictions recently eased, the day after the forum laboratory testing by the Central Iowa Water Works in Des Moines still showed unsafe high levels of nitrates in water samples from the Raccoon River, one of the two main rivers that supplies the area’s drinking water.

A spokeswoman said the utility was currently drawing from other water sources due to the nitrate levels in the river.

State officials generally point the finger at smoking, alcohol use and other factors as driving the cancer rates, and have been reluctant to look too hard at agriculture, according to Adam Shriver, director of wellness and nutrition policy at the Harkin Institute at Drake who helped lead the drinking water forum this week.

“That part of the conversation [agriculture] oftentimes gets pushed down and pushed away,” he said. “Iowa has a long history of basically putting the thumb on the scale when it comes to looking at issues related to agriculture and public health.”

But public support for new regulations on agriculture appears to be growing, Shriver said.

“People want a course correction. They are not satisfied with what is being done now,” he said. “They’re tired of being told ‘oh yeah everything is fine, don’t worry about it.’”

“Something in the water”

Angela Connolly, a Polk County supervisor who has served in office since 1998 and who attended the Monday evening meeting, is among those whose patience has run out when it comes to Iowa’s water pollution problems.

“This was the largest crowd I’ve ever seen on a single subject,” she said. “We have to show the political will. We have to go to the state house and demand change for water quality.”

Connolly said her 47-year-old daughter-in-law has suffered from breast and colon cancer, and she knows of several other people in their 40s also suffering from cancer.

“I truly believe that there is something in the water and I want something done about it,” she said.

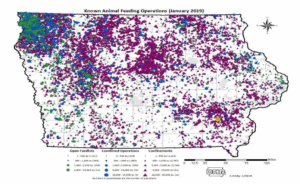

With nearly 87,000 farms, Iowa is a key producer of many agricultural products, ranking first in the production of corn, pork and eggs, and within the top five states for growing soybeans and raising cattle. Of Iowa’s 35.7 million acres of total land, roughly 31 million is devoted to farming. Agriculture contributes close to $160 billion to the state’s economy – roughly one-third of the state’s total economic output, according to the Iowa Farm Bureau.

“We have to show the political will. We have to go to the state house and demand change for water quality.” – Angela Connolly, Polk County official

Many farmers are among the voices calling for changes to help mitigate the pollution fouling the waterways. Those relying on private well water say they feel at particular risk from pollutants that are so prevalent in rural areas.

Seth Watkins, who traveled 120 miles from his farm west of Des Moines to attend the drinking water forum, said he has altered his farming practices to reduce contributing contaminants to the watershed, but still worries about the water – not just for his family, but also for his livestock.

He questions whether the chemicals contaminating the area contributed to the fact that both his children were born with health challenges.

“It would be great if we could do this voluntarily, but I don’t know any society in the history of mankind that has actually protected our natural capital without some level of enforceable regulation,” Watkins said.

“Going backwards”

A particular point of concern when it comes to water contamination is the abundance of large concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) across the state that regularly generate large quantities of manure, and related agricultural businesses such as slaughterhouses.

Despite pleas from environmental groups, state officials have shown continued support for the animal operations.

In one contamination case angering Iowans, Agri Star Meat and Poultry, which operates a beef and poultry slaughterhouse in Postville, Iowa, was found to have exceeded wastewater limits roughly 60 times, leading to “acutely toxic concentrations” of ammonia in area waterways. The operation also failed to comply with monitoring and reporting requirements, according to a July 30 announcement from the Iowa Attorney General’s office.

The state has ordered the company to pay a $50,000 penalty and given it until the end of 2026 to come into compliance. The action by the state came after a local nonprofit sued Agri Star for allegedly violating water quality laws.

In another agricultural contamination case, NEW Co-op is paying a $50,000 fine for an ammonia nitrogen release last year that caused a “significant” fish kill along 48 miles of the Nishnabotna River that flows as a tributary of the Missouri River in southwestern Iowa.

As part of the settlement with the state, the company agreed not to violate Iowa’s water quality laws for three years.

The fertilizer spill that caused the fish kill sparked farmer Denise O’Brien, who lives with her husband on the farm he grew up on in Atlantic, Iowa, to join with others in her area to start the Nishnabotna Water Defenders. The nonprofit focuses on monitoring and protecting the water quality in their region and is training people to test water and push for polluter accountability.

O’Brien said her mother and sister died of cancer and several neighbors suffer from ovarian, breast and pancreatic cancers as well as Parkinson’s disease. She and her husband drove with neighbors an hour and a half to attend the water forum.

“Our public officials don’t have a political will,” she said in an interview following the forum. “There’s a lot of groundwork to do, not only testing water, but encouraging people to be involved politically, because people are just giving up … we’re going backwards now.”

In concluding the forum, organizers asked attendees to sign up for training to help with both water quality monitoring and with public advocacy efforts, and an environmental group offered free water testing kits for people to collect nitrate readings in their communities. The audience responded with a standing ovation. The song “Bridge Over Troubled Water” played as they trailed out of the auditorium.

(Featured photo of the Raccoon River in Des Moines, Iowa, on Aug. 5, 2025. Photo by Carey Gillam.)