“How can this happen?” Fight over sewage sludge on farms intensifies

Ryan Dunham heard his eleven-year-old daughter’s scream from his living room. He bolted up the stairs to the bathroom where she was taking a shower and couldn’t believe his eyes. The water flowing from the faucet was brown, and it smelled like “decay, rot and death.”

It was the same smell he noticed coming from his neighbor’s farm fields across the street just days earlier. Dunham has lived in New Scotland, a rural town in upstate New York, for more than 20 years and is accustomed to the smell of manure. But this smell was different, it was so bad he couldn’t open his windows and his kids didn’t want to play outside in the middle of summer.

After that day last spring, Dunham discovered his neighbor was spreading sewage sludge — a biosolid made up of decomposed human and industrial waste — as fertilizer on the fields. That waste was seeping into his home’s water supply, putting his family’s health at-risk.

“I connected the dots that my kids were literally taking showers in human sewage,” Dunham said. “How can this happen in the state of New York? How can this happen legally in the United States of America? It boggles my mind.”

The practice of using sewage sludge as fertilizer on agricultural land has long been promoted by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), waste management companies and municipalities as a climate-friendly and inexpensive way to recycle the remnants of public waste in a manner that provides value to farmers. According to an analysis of surveys from biosolids industry groups, sludge is spread on almost 70 million acres of US farmland.

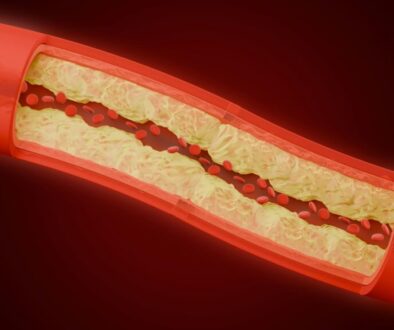

But evidence has mounted in recent years showing that sewage sludge can contain high concentrations of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), a class of widely used chemicals that have been linked to various types of cancer, thyroid disease, liver damage and other health problems.

In January, the EPA confirmed for the first time that even at extremely low levels, two types of PFAS – perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS) – in sewage sludge applied to farmland could result in an elevated risk of cancer.

The National Association of State Departments of Agriculture has cited PFAS as a “major hazard” for US farmers and ranchers. But it’s not just farmers at risk. Livestock and crops raised on contaminated fields and sold to the public can be contaminated with PFAS, and researchers have found that runoff from farm fields carry PFAS into waterways where the chemicals can show up in household water supplies, as Dunham experienced.

“This is an issue that affects ecosystem health, human health, drinking water, hunting, farming, recreation, and it’s also one that doesn’t respect state borders,” said Clare Walsh Winsler, the director of food, policy, and land use at Environmental Advocates New York, an organization fighting for stricter biosolid regulation.

“PFAS doesn’t care if you live in Massachusetts or Connecticut. They don’t care if you’re in New Jersey or New York,” Walsh Winsler said. “These chemicals spread and they bioaccumulate in living organisms, from plants, to beef cattle, to ourselves.”

Deep pockets

Amidst pressure from advocates and affected communities, the Biden administration was taking steps to more closely regulate the issue. They released the first-ever EPA preliminary evaluation of the human health risks associated with PFAS in biosolids, as well as funded landmark research into the issue across the country. But now, The Trump administration is moving to reverse course.

As it slashes funding and research related to environmental protection, public health advocates say regulating sewage sludge at the state and local level has become critical.

In early June, the EPA met with representatives from an industry trade group established by the waste management company Synagro Technologies Inc., which is currently being sued by farmers in Texas who allege the company’s sludge contaminated their field with PFAS.

According to meeting notes, the group was to share their thoughts on the EPA’s landmark January Draft Risk Assessment on PFAS in biosolids, and “ensure validated science” was being used to develop federal regulations.

Just weeks later, congressional Republicans proposed a permanent provision in a House appropriations bill that would prevent funds from being used to finalize the risk assessment, as well as prevent any PFAS regulation on biosolids based on the report’s findings.

“These are deep pockets, and deep pockets mean that EPA is susceptible to influence, because industry influences EPA all the time,” said Kyla Bennett, the director of Science Policy at Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility.

Though long overdue, the EPA’s risk assessment was crucial in supporting the urgent need for biosolid regulation at all levels, Bennet said. The report confirmed that two types of PFAS widely found in sewage sludge can contaminate the milk, eggs and meat coming from farm animals where sewage sludge is spread. It also confirmed land spreading “could result in human health risks exceeding the agency’s acceptable thresholds for cancer and noncancer effects.”

Several other limits from the risk assessment were expected to be implemented this year, but the rider could put those on hold too.

“Couple this with his [Trump’s] attempts to stop funding of research into this, it’s all a gift to the industry,” Bennett added.

In July, Trump cut nearly $15 million in research into PFAS contamination on US farms, closing studies at 11 universities across the country. The research was the result of a 2024 federal lawsuit against Biden’s EPA, alleging that water pollution stemming from PFAS contamination violates the Clean Water Act.

Bennett, along with advocates at the state level, fear this lack of federal oversight will create a discrepancy in uniform biosolid regulation across the country, with red states likely struggling most to protect their food and water supply. “I mean, that’s the whole reason we have a federal EPA, so that we have some kind of floor, so that the whole country can be safe right?” she said.

“Don’t worry about it”

As awareness of the public health risk grows, and with a lack of aggressive federal action, state and local authorities across the country have been pushing for regulatory action and investigations into sewage sludge spreading.

In 2022, Maine became the first state to ban sewage sludge use and launch statewide testing into PFAS contamination on farms. Connecticut followed in 2024, and several other states, including New York, Texas, and Oklahoma are considering legislation to ban or restrict the land application of sewage sludge, which is often referred to as biosolids.

But even in a blue state like New York, the waste management industry holds immense influence, and regulating sewage sludge is not an easy task. New York currently ranks among the top five states spreading biosolids on land, according to the National Biosolids Data Project.

The New York State Department of Environmental Conservation plans to increase the use of biosolids from 22% to 57% percent by 2050, claiming sludge is a “nutrient-rich” organic material that’s beneficial for farmers.

New York State Assemblywoman Anna Kelles, who holds a PhD in nutrition, said this is the equivalent of telling a person “Here is this protein shake with all the nutrients you need … it’s just got a little arsenic in it, but don’t worry about it, we’ll deal with that later!”

A number of municipalities across New York have found elevated levels of PFAS and other contaminants in waterways and private wells nearby fields where sewage sludge was spread.

In New Scotland, where Dunham lives, water samples from his well, along with 10 of his neighbors’, tested nearly 200 times above the safe limit for E. coli and coliform. In the nearby town of Bethlehem, PFBA, a PFAS chemical found in the sewage sludge spread by Dunham’s neighbor (and one that’s not regulated by the EPA) was detected in the town’s water supply.

Elevated PFAS levels have also been detected in private wells in Thurston, Cameron, and Bath, all located in Steuben County. In response to the findings, Thurston implemented, and later renewed, a one-year ban on the use of sewage sludge in land applications.

This past year, Kelles and State Senator Pete Harckham introduced legislation that would put a statewide, five-year moratorium on sewage sludge spreading. The bill passed all four committees of the state legislature, but unexpectedly stalled on the Assembly floor, despite early bi-partisan support.

Kelles said she suspects this last-minute flip is the result of lobbying efforts from a division of Denali Water Technology, WeCare Denali, which has a more than $2 million contract with Rockland County. WeCare Denali is owned by the $19 million private equity firm, TPG.

“The lobbying efforts are coming from these companies, and they’re hiding behind local county governments,” Kelles said.

WeCare Denali did not respond to a request for comment.

A number of municipalities and counties across New York State have contracts with waste management companies including Casella, Synagro and Denali, and have invested in infrastructure to support biosolid spreading. Some argue the moratorium would leave these municipalities without an alternative form of waste disposal.

But for residents like Wayne Miller, the health and safety of his family is more important than delayed progress. He lives on an organic farm in Franklin County, about 30 miles from the Canadian border, and has been advocating for stricter biosolid regulation as part of the Sierra Club’s Atlantic Chapter.

Knowing that PFAS could be entering the food chain through the spreading of biosolids is horrific for Miller, whose grandchildren live next to a farm field. “Forever chemicals are going to live with my grandsons,” he said. “That’s, that’s a big part of why I’m doing this.”

The Sierra Club and several other environmental advocacy organizations in New York are building a statewide coalition of farmers, residents, and bi-partisan legislators to try to ensure the moratorium on sewage sludge spreading passes in the next legislative session, which will resume in January.

But without stricter federal regulation on PFAS at the federal level, state regulation is just a temporary fix, said Walsh Winsler of Environmental Advocates New York.

“Without any type of regulation or risk assessment at the federal level, it leaves a patchwork of regulation at the state level … we need federal action,” she said.

For Dunham, the legal and political battles are far removed from his daily fears for his family’s health.

“Whenever my daughter’s taking a shower and singing Taylor Swift, I wonder what chemicals she is ingesting,” he said. “And what future health issues are going to be caused by that?”

(Featured photo from Environmental Advocates New York.)