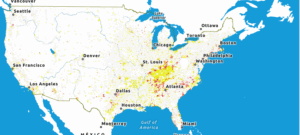

New maps reveal 73 million people exposed to PFAS in US drinking water above EPA standards

Over 73 million people in the US are being exposed to toxic PFAS chemicals in their tap water, according to an analysis of data from a US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) water monitoring program.

Unsafe levels of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) have been found in excess of EPA thresholds in every US state but Arkansas, Hawaii and North Dakota, according to the analysis published July 17 by the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC).

NRDC released maps built on the data, and said the research shows that people across the country will be impacted by an EPA plan to rescind drinking water limits for four PFAS chemicals and push back compliance deadlines for two others.

The Trump administration reversed plans announced under President Joe Biden a little more than a year ago to set enforcement limits for the six PFAS chemicals.

Exposures to some types of PFAS have been linked to certain cancers, thyroid disease, liver damage and immune system problems, among other health problems.

“We all expect that when we turn on the tap that water is going to be safe for our families to consume,” said Katie Pelch, a senior NRDC scientist and one of the maps’ creators. “EPA’s actions are going to place a really heavy financial and health burden on the communities all across the nation.”

While the agency’s data includes 29 different PFAS chemicals, most of which are not regulated in drinking water, the NRDC maps home in on reported levels of the six PFAS subject to regulatory changes – perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS), perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA), perfluorohexane sulfonate (PFHxS), perfluorobutane sulfonate (PFBS) and GenX.

Even more people might be affected by the EPA’s change of course than estimated, added Pelch, since the EPA monitoring program excludes many smaller water systems. Additionally, the federal data collection is ongoing through 2025, with EPA releasing about 75% of reporting results as of June.

“Especially concerning”

While the creators of the NRDC map characterized the data as just “the tip of the iceberg,” the mapping tool can help people across the US understand where PFAS have been measured, said Alissa Cordner, co-director of the PFAS Project Lab at Northeastern University who was not involved in making the maps.

The current EPA proposals to roll back the health-based drinking water standards “are especially concerning given how widespread PFAS contamination is,” said Cordner.

The new maps come as the suspension period for a lawsuit challenging the EPA’s PFAS drinking water standards comes to a close. After President Donald Trump took office, the court granted the agency’s request to suspend the case, allowing the new administration to decide whether to defend the drinking water standards established under President Biden.

The abeyance of the case concludes July 21, at which point the EPA may either explain how it plans to proceed with the PFAS drinking water standard rollbacks it announced in May or request to continue suspending the case, according to the NRDC.

Treatment plants and sewage sludge

The NRDC maps follows a separate report issued last month by the Waterkeeper Alliance and the Hispanic Access Foundation that assessed how wastewater treatment plants and fields where sewage sludge is applied as fertilizer contribute to PFAS contamination in surface water.

Researchers measured PFAS in surface water near 22 wastewater treatment plants and 10 fields where sludge had been applied, focusing on sites near communities disproportionately impacted by PFAS contamination in 19 states.

The analysis found at least one type of PFAS in 98% of sites sampled, frequently detecting the chemicals at levels above federal drinking water limits.

The report “further demonstrates that treatment processes and land application methods play a critical role in the release of these contaminants into surface waters,” the report states.

To measure PFAS near the treatment plants and contaminated fields, the researchers deployed passive PFAS sampling devices both upstream and downstream of the sites, which measured levels of the toxic chemicals over the span of 20 days, according to the report.

“To the best of our knowledge, none of the [wastewater treatment plants] identified in this report have installed treatment technologies to remove PFAS from either their wastewater discharged to surface waters or their biosolids,” the authors wrote, noting that the majority of the facilities they analyzed are not required to monitor or limit PFAS levels in sewage sludge before it is applied to land.

While sewage sludge is treated prior to land application, traditional treatment technologies do not remove PFAS chemicals.

(Featured image by Lia Bekyan via Unsplash.)