Seeking answers to a cancer crisis in Iowa, researchers question if agriculture is to blame

INDIANOLA, Iowa – Six months ago, Alex Hammer was diagnosed with colon cancer at the age of 37. Dianne Chambers endured surgery, chemotherapy and dozens of rounds of radiation to fight aggressive breast cancer, and Janan Haugen spends most days helping care for her 16-year-old grandson, who is still being treated for brain cancer he developed at the age of 7.

The three were among a group of about two dozen people who came together last week in Indianola, Iowa, to share their experiences with rising rates of cancer plaguing the state. The event in the town of about 16,000 residents was the first of 16 “listening” sessions scheduled around Iowa as part of a new research project aimed at investigating potential environmental causes for what some call a cancer “crisis.”

As a key US farm state, Iowa has long been known for the leafy green stalks of corn that stretch seemingly endlessly across the horizon. With nearly 87,000 farms, the state ranks first not only for corn production but also for pork and egg production, and is within the top five states for growing soybeans and raising cattle.

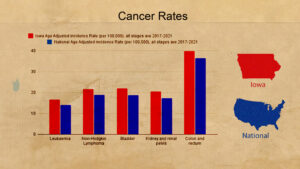

But the state holds a darker, more ominous ranking as well: For the last few years, Iowa has ha d the second-highest rate of cancer in the nation, and is only one of two US states where cancer is increasing. Leukemia, as well as cancers of the pancreas, breast, stomach, kidney, thyroid and uterus, are among the different cancer types on the rise across the state, according to the National Cancer Institute.

d the second-highest rate of cancer in the nation, and is only one of two US states where cancer is increasing. Leukemia, as well as cancers of the pancreas, breast, stomach, kidney, thyroid and uterus, are among the different cancer types on the rise across the state, according to the National Cancer Institute.

“People in rural communities are getting sick. Cancer is just everywhere,” said Kerri Johannsen, senior director of policy at the Iowa Environmental Council (IEC). Johannsen grew up on a family farm in the northeast part of the state, where her brother and parents grow corn and soybeans and raise cattle.

“Every person I talk to knows somebody that has [recently] had a cancer diagnosis,” she said. “It’s just a constant drumbeat. It’s scary.”

The high cancer rates are the driver behind a new initiative to study the “relationship between environmental risk factors and cancer rates” led by the IEC and the Harkin Institute at Drake University.

Among the initiative’s key suspected culprits are the chemicals that flow from Iowa’s vast expanse of farmland.

“Honing in” on agriculture

Kentucky, the only state with a higher cancer incidence than Iowa, historically has also ranked first in adult smoking, which is considered as having a major role in the state’s high cancer rates.

In Iowa, the search for a cause has been less clear. Last year, a state report cited alcohol consumption as a key factor. Higher-than-average levels of radon, a naturally occurring, colorless gas known to cause cancer, are also a concern.

But many blame the insecticides, herbicides and other pesticides widely used on farms as well as the state’s persistent problem with high levels of hazardous nitrates that wash off farm fields into the state’s water supply. Of Iowa’s 35.7 million acres of total land, roughly 31 million is devoted to farming.

Many of the pesticides routinely used are linked to a range of diseases, including the popular herbicide glyphosate, which is classified a probable human carcinogen by cancer experts at the World Health Organization. Nitrates are also tied to cancer, particularly when consumed in drinking water or other dietary sources.

Agricultural fertilizers and manure from large-scale livestock operations are key sources for nitrates, which are known to contaminate surface water and groundwater.

In addition to looking at pesticides and nitrates, the research will also look at cancer links to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS).

PFAS are pervasive globally, and one emerging concern has been PFAS contamination of sewage sludge spread on farm fields as fertilizer. Earlier this year, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) warned of elevated cancer risks related to such contaminated farm fertilizer.

The work will also include a deeper look at the state’s high levels of radon as a key cancer cause, said Elise Pohl, former community health consultant for the Iowa Department of Health who is the lead researcher for the project.

“We really want to find out why these cancers are increasing,” Pohl said. “We’re honing in on the agriculture side of things.”

“Elephant in the room”

The focus on agriculture is controversial, according to Adam Shriver, director of wellness and nutrition at the Harkin Institute who is helping lead the initiative.

Agriculture contributes an estimated $159.5 billion to the state’s economy – roughly one-third of Iowa’s total economic output, according to the Iowa Farm Bureau. And the industry influence is potent, according to Shriver.

There is a lot of pressure from state leaders as well as within research circles not to point fingers at agriculture. But increasingly, residents are expressing fear that the industry providing Iowa’s economic lifeblood may also be killing them, he said.

“In most people’s minds, you escape to the country for healthy, clean living and yet … the elephant in the room is that we’ve been practicing industrial agriculture and we’ve had a government that has been subservient to big agriculture and they’ve been allowed to do whatever they want,” Shriver said.

Iowa Farmers Union policy director Tommy Hexter said many farmers are worried about the health impacts of their use of pesticides but are reluctant to be too vocal.

“We have a lot of folks who are conventional farmers who are concerned about this,” said Hexter. “They’re worried about cancer in their families. But they don’t want to be outspoken about an industry that supplies them essential tools.”

Several farm organizations were asked for their views on the new study and fears of ties between agriculture and cancer, but only one, the Iowa Corn Growers Association, responded.

“We’re interested in looking at all potential causes of cancer,” said Rodney Williamson, the association’s vice president of research and sustainability. He cited smoking, radon, obesity, tanning beds, and alcohol as additional potential causes to consider. “We should be looking at all of those.”

He said when it comes to pesticides, the association urges farmers to follow the recommendations of the EPA, which does “an extensive review” of pesticides for potential carcinogenicity, and to ensure that they apply pesticides appropriately.

Wondering and worrying

At last week’s listening session in Indianola, the moderator asked attendees to raise their hands if they had experienced cancer personally or through someone close to them. Everyone raised a hand.

At last week’s listening session in Indianola, the moderator asked attendees to raise their hands if they had experienced cancer personally or through someone close to them. Everyone raised a hand.

In sharing his story with the group, Hammer, now 38, said his diagnosis of colon cancer stunned him. He had been a healthy long-distance runner with no genetic markers for the disease. After extensive surgery, the cancer now appears cured, he said. He wonders if the cancer may be tied to his childhood attendance at schools surrounded by corn fields.

Haugen, whose grandson suffers from brain cancer, attended the session with her husband. She helps the boy’s mother and other relatives transport him to and from treatments that so far have included multiple brain surgeries and extensive chemotherapy. She said the disease that has nearly killed the boy seems far too common for their small town.

“There are several kids here that have cancer,” Haugen said.

Chambers, who was diagnosed with breast cancer at the age of 50, lives about 20 miles south of Indianola where she and her husband farm roughly 1,000 acres. She said many others in her area have also suffered from cancers, and though she does not know what caused her illness, which is now at bay, she stays far from farm chemicals.

“Do I think it’s chemicals? Do I worry about the water?,” she asked rhetorically. “I do.”

Funded with donations from individuals and foundations, the research team plans to produce a report based on a broad review of years of published scientific studies as well as the anecdotal information gleaned in the listening sessions. The researchers hope to release some initial findings later this year.

Dr. Richard Deming, a cancer doctor in Iowa for 36 years, said he donated personal funds to the project because he feels more independent research is needed to inform policies that can help cut the cancer rates.

“It’s not trying to throw any industry under the bus,” he said. But, lots of people now are scratching their heads and wondering what can we do to further determine the incidences and then how do we mitigate. As a cancer doctor taking care of patients, I have the opportunity one patient at a time to try to help … But if you can prevent cancers you can actually make a bigger difference than treating each cancer that comes into your office.”

(A version of this story was co-published at The Guardian.)

(Featured photo by Veronica White on Unsplash.)

June 24, 2025 @ 9:00 am

We seem to always assume the link between obesity and [fill in the blank] is that obesity causes the other. It’s my understanding that there are very few studies not funded by the weight loss and wellness industry looking at whether comorbid issues might be contributing to the rise in obesity across the world.

June 23, 2025 @ 2:41 pm

An excellent point which should spur further research into parallels between rising cancer rates and rising use of glyphosate based on locality. The farmers as the article stated have remained on the quiet side but the impact of cancer on themselves and their families needs to be documented along with shifts over time in their farming practices. All the while I’m wondering what is this doing to the food? I buy organic. I’m not taking any chances for my family or friends.

June 21, 2025 @ 11:10 pm

Yes and have ppl who live near farms where these chemicals are used included in studies. The cohort should all have their well water tested and discover heavy metal levels, changes to protein structures, epigenetic, genetic as well as a full intake re not only cancer but symptomology. We need better diagnostics for GI disorders and connective tissue dysfunction and hormone dysregulation. Daughter of a conventional farmer here. He finally began to comprehend the danger in his final years and came to terms with his story of how both his community, and the industry of farming both gave him purpose in life, and also put him at risk. He passed of cancer (with other medically complex conditions) and experienced a medical crisis each time he sprayed and/or dried the corn.

We are back in farming country again, and my family knows to filter our well water and the importance of not allowing dust from near by fields to accumulate indoors.

June 21, 2025 @ 10:38 am

They must only review up to 2021. Any study that includes anyone that has had a reoccurrence or developed cancer after 2021 must include if they received the Covid vaccine. Insurance companies and studies have seen connections to the vaccine with cancer increases. Especially with fast growing turbo cancers in the last few years.

Including PFAS in the study is smart. People worried about drinking well water have switched to bottled water.

June 18, 2025 @ 12:56 pm

“He cited smoking, radon, obesity, tanning beds, and alcohol as additional potential causes to consider. ‘We should be looking at all of those.’ ”

OK, which ones of these have increased in the last 20-30y, presumably along with cancer. Probably only obesity and pesticides. My guess is that they should compare populations based on weight, occupation, and whether they farm organically, and if so for how long.