Postcard from California: After the fires, is LA safe from buried toxic hazards? Don’t ask FEMA

After a wildfire wiped out the northern California town of Paradise in 2018, federal and state disaster recovery crews took exhaustive efforts to determine if it was safe for residents to move back.

After a wildfire wiped out the northern California town of Paradise in 2018, federal and state disaster recovery crews took exhaustive efforts to determine if it was safe for residents to move back.

First, the US Army Corps of Engineers scraped six inches of topsoil from burned lots to remove lead, arsenic and other hazardous chemicals. Then, contractors dug even deeper to collect soil samples to test for remaining toxic hazards. When tests showed that about a third of the deeper samples still had dangerous levels of chemicals, crews excavated more layers of soil, in some cases going back multiple times before declaring a site safe.

Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) paid for 75% of the $3 billion cost of cleanup. But in the wake of the fires that in January burned more than 16,000 homes, schools and businesses in Los Angeles County, FEMA has repeatedly refused to fund sampling and testing to confirm safety.

FEMA never announced that it would not pay for so-called confirmatory sampling, which was revealed only after a query from the Los Angeles Times. In response, California Gov. Gavin Newsom formally requested FEMA to pay for confirmatory sampling, which he said the agency has done after most major urban fires for decades – most recently, the inferno that leveled Lahaina, Hawaii, in August 2023.

Less than 24 hours later, FEMA again said no. A similar request from seven members of Congress from southern California went unanswered.

The agency maintains that removing six inches of soil is enough, that deeper contaminants are probably naturally occurring, and that it’s not the federal government’s responsibility to ensure that the soil meets strict California safety standards. FEMA stopped funding post-fire confirmatory sampling in 2020, but an exception was made in Hawaii because of a lack of data on naturally occurring contaminants there.

So far, California, facing a $12 billion budget deficit, has not paid for confirmatory sampling. In a May 29 email to The New Lede, a spokeswoman for the California Environmental Protection Agency said the state “continues to push for our federal partners to conduct comprehensive soil sampling as part of the debris removal process.”

FEMA’s denial and the state’s lagging response have left toxics experts and homeowners, who may have to pay for sampling themselves, fearful of what lies beneath the thousands of burned lots.

“If they’re not willing to do confirmatory sampling, that tells us they’re willing to leave the properties contaminated,” Jane Williams, executive director of California Communities Against Toxics, told the Los Angeles Times. “They’re willing to leave people at risk.”

In the face of FEMA’s refusal and the state’s inaction, in May the Times launched its own confirmatory sampling initiative. Journalists collected soil samples from dozens of burned lots in greater Los Angeles and sent them to a certified lab for testing.

In Altadena, a Pasadena neighborhood where fire destroyed more than 6,000 homes, two of ten sites cleared by federal crews had levels of toxic chemicals above state safety standards, including one with lead more than three times higher than the benchmark.

Based on historical data from other fires, the Times estimated that more than a thousand cleared properties still contained potentially dangerous levels of toxic chemicals. But the danger isn’t confined to sites that burned. The fires sent huge clouds of toxic contaminants airborne. The contaminants then settled on yards, parks, school grounds and other public places.

The Times’ tests revealed elevated levels of lead, arsenic and mercury in the yards of three of 20 homes that survived the fires in Altadena and the Los Angeles neighborhood of Pacific Palisades. Tests by Los Angeles County found that 44% of such sites in Altadena and 12% in the Palisades had lead levels above state standards.

Scientists from the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) also found elevated lead levels on lots up to seven miles from the Altadena fire’s perimeter. Altadena homeowner Anita Ghazarian told the Times the contamination is “a calamity waiting to unfold.”

After the Times and the county released their results, the Pasadena school district released more alarming test data: More than half of the district’s 23 campuses had levels of lead, arsenic, chromium or other heavy metals higher than state standards or what the county deems acceptable for residential soil.

The district’s more than 14,000 pupils have been back on campus since the fires were contained Jan. 31, potentially exposing them to a brain-damaging chemical lead for which the federal Centers for Disease Control and Protection says there is no safe level in children’s blood.

Although with the exception of the Hawaii fires, FEMA stopped confirmatory sampling five years ago, the refusal to pay for it in Los Angeles is of a piece with the recent retrenchment of federal disaster response by the Trump administration.

In January, while touring flood damage in North Carolina, President Trump said “I think we’re going to recommend that FEMA go away.” Visiting Los Angeles after the fires, he said, “You don’t need FEMA, you need a good state government.”

Trump has since denied requests for aid following flooding in West Virginia, a windstorm in Washington state, and other severe weather. He initially denied Arkansas’ request for aid after widespread tornadoes, relenting only after a personal plea from Arkansas Gov. Sarah Huckabee Sanders, his former press secretary. Other states have complained of months-long waits for help.

In May, the acting head of FEMA, Cameron Hamilton, was fired a day after testifying before Congress that he did not think eliminating the agency was “in the best interest of the American people.”

“Communities look to FEMA in their greatest times of need,” he told lawmakers, “and it’s imperative that we remain ready to respond to those challenges.”

Under his successor, David Richardson, the agency is in turmoil. Its staff has been cut by a third, and it faces a backlog of unprocessed aid requests as hurricane season approaches.

“I’m very worried about what the next few months look like for communities that are going to be impacted by a wildfire, or a tornado, or a hurricane, or a flood,” Rob Moore, a policy analyst at the nonprofit Natural Resources Defense Council, told Government Technology magazine. “The assistance that we have come to rely upon is no longer there. It’s just not there.”

- Bill Walker has more than 40 years of experience as a journalist and environmental advocate. He lives in California’s San Joaquin Valley.

(Opinion columns published in The New Lede represent the views of the individual(s) authoring the columns and not necessarily the perspectives of TNL editors.)

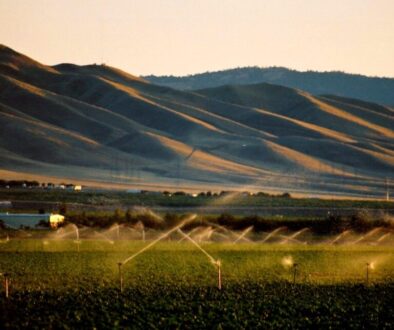

(Featured photo by Wolfgang Hasselmann on Unsplash.)