Even long after close of polluting paper mill, study finds area residents with high levels of toxins in their blood

Residents of a Michigan community whose drinking water was polluted with toxic chemicals from a long-shuttered paper mill continue to have high levels of the compounds in their bodies, even years after the community switched to alternate water supplies, according to a new study.

A team led by researchers from Michigan State University (MSU) measured levels of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in blood samples taken from people living in the area of Parchment, Michigan, coming up with data the researchers said underscores how difficult it is to purge PFAS from the bodies of people exposed to them.

PFAS, also known as “forever chemicals” because of the difficulty in eradicating them, are a class of chemicals that include several types linked to cancers and other health concerns. Two of the types known to be particularly hazardous, perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS), were found in 100% of the blood samples.

“This research highlights how vulnerable our drinking water systems can be to contamination from old paper mills or landfills,” Heather Stapleton, a co-author of the study and a professor at Duke University, said in a statement. “Likely, this city is not alone. Other cities or regions could be just as vulnerable. This work underscores the importance of routine monitoring for contaminants in our drinking water.”

A contamination emergency

The study is one of many showing PFAS persistent in the blood of both people and animals. PFAS have become ubiquitous in the environment after decades of use in popular consumer goods as well as in an array of industrial processes and heavy use in firefighting foams. A 2022 analysis found detectable levels of PFAS in about 83% of US waterways. The chemicals are frequently found in drinking water.

World governments and public health advocates are pushing to sharply limit exposure to PFAS. In the US, the Biden administration issued a drinking water rule requiring public water systems to implement technologies to reduce PFAS in their water supplies by 2029 if levels exceeded certain limits. But environmental advocates are concerned that the Trump presidential administration may weaken those protections.

Rainer Lohmann, director of a PFAS research center based at the University of Rhode Island, said the study adds to evidence that drinking water is a “key exposure pathway, and that the compounds linger for a long time.”

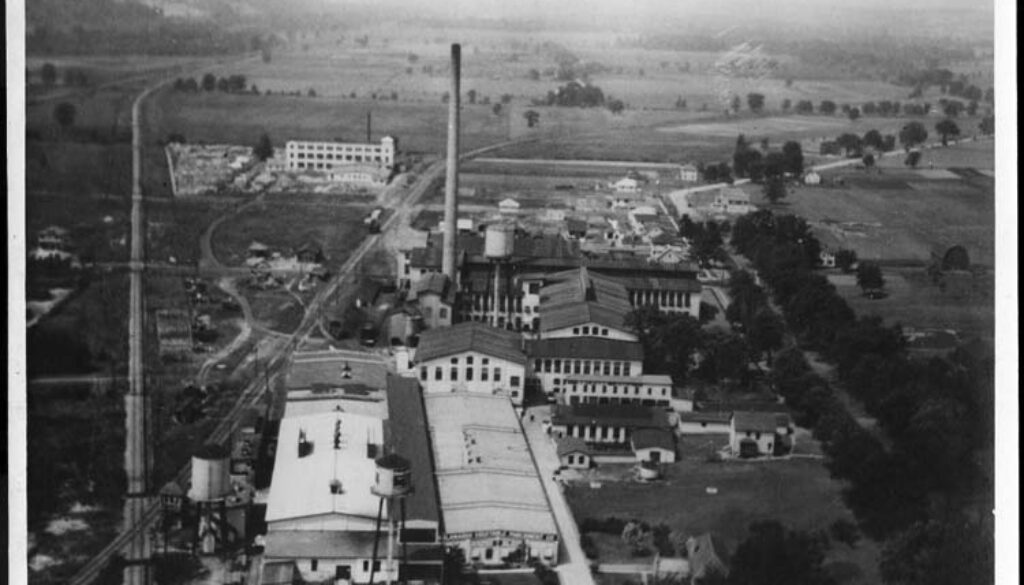

The new study targeted a community known to be contaminated by a former paper mill that operated from 1909 to 2000. The mill used an oil and grease repellant chemical as an additive to its laminated paper products and disposed of the waste in an area landfill.

State regulators declared a state of emergency there in 2018 after finding unsafe high levels of PFAS compounds in the city’s municipal water supply, forcing the city to switch to a separate water supply. Private wells were also found to contain high PFAS levels. In 2021, 3M and Georgia-Pacific agreed to pay $11.9 million to settle litigation over the contamination.

Collecting blood

In conducting the new study, researchers recruited people who lived in the area between 2005 and 2018 and consumed tap water. They visited the homes of 100 participants, collecting blood and water samples, as well as asking people to provide information about their water source and filtration and residential history.

Of 80 study participants selected for the analysis, 39 were part of a high exposure group, defined as people who received municipal water for at least a year from 2005-2018, while 41 were in a low exposure group of people who received water from a private well prior to 2018.

The longer the participants drank city water, the greater the risk, the researchers found.

“The water source was found to be the strongest predictor of PFAS levels in blood, which increased for every additional year of drinking the water,” the study states.

Sampling identified continued concentrations of PFAS in public water in 2022, the researchers said.

The study “highlights the persistence of PFASs and the risk that abandoned landfills can pose to drinking water in nearby communities,” the study authors concluded. “These data establish a baseline for long-term toxicological impacts and evaluation of intervention effectiveness.”

(Featured photo is an aerial view of the Kalamazoo Vegetable Parchment Company, a paper mill in Parchment, Michigan. Photo courtesy of Michigan State University Libraries.)