High levels of microplastics found in human brains

By Douglas Main

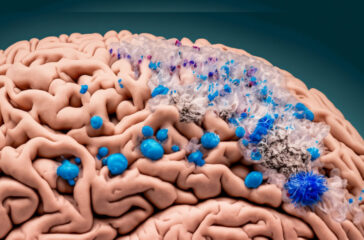

A new study has found high concentrations of tiny plastic particles in human brain samples, with levels appearing to climb over time.

By Douglas Main

A new study has found high concentrations of tiny plastic particles in human brain samples, with levels appearing to climb over time.

By Carey Gillam

People diagnosed with infertility and certain cancers may have to blame the very air they breathe, according to a new report that adds to evidence that tiny plastic particles in air pollution and other environmental sources could be causing these and other diseases and illnesses.

By Carey Gillam

Exposure to a widely used weed killing chemical could be having “persistent, damaging effects” on brain health, according to a new study.

By Carey Gillam, Margot Gibbs and Elena DeBre

In 2017, two United Nations experts called for a treaty to strictly regulate dangerous pesticides, which they said were a “global human rights concern”, citing scientific research showing pesticides can cause cancers, Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s, and other health problems.

By Douglas Main

A growing body of scientific evidence shows that microplastics are accumulating in critical human organs, including the brain, alarming findings that highlight a need for more urgent actions to rein in plastic pollution, researchers say.

By Carey Gillam

California has moved a step closer to banning the controversial weed killing chemical paraquat after a key state legislative committee on Thursday allowed the measure to proceed.

![High_res_image-Syngenta_Group_-_HQ_-_Basel_-_Switzerland[1] High_res_image-Syngenta_Group_-_HQ_-_Basel_-_Switzerland[1]](https://www.thenewlede.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/High_res_image-Syngenta_Group_-_HQ_-_Basel_-_Switzerland1-1024x682-364x240.png)

By Carey Gillam

Global chemical giant Syngenta has sought to secretly influence scientific research regarding links between its top-selling weed killer and Parkinson’s, internal corporate documents show.

By Carey Gillam

When US regulators issued a 2019 assessment of the widely used farm chemical paraquat, they determined that even though multiple scientific studies linked the chemical to Parkinson’s disease, that work was outweighed by other studies that did not find such links. Overall, the weight of scientific evidence was “insufficient” to prove paraquat causes the brain disease, officials with the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) declared.

By Carey Gillam and Aliya Uteuova

For more than 50 years, Swiss chemical giant Syngenta has manufactured and marketed a widely used weed killing chemical called paraquat, and for much of that time the company has been dealing with external concerns that long-term exposure to the chemical may cause the dreaded, incurable brain ailment known as Parkinson’s disease.